Mary Magdalene in Gaul

It was June 2018 when Mary Magdalene strolled into my consciousness. I vowed to go to France, giving myself the arbitrary date of October 2019 – my birthday month. I did not know where I needed to go (or why) but I knew it was important to go there physically.

Incredibly, this dream came to fruition, when in August 2019 my mother invited me to walk the Camino de Santiago with only 6 weeks to prepare. Using intuition and where I have been guided to research, I planned our trip in the Languedoc region, contained within the modern-day region of Occitanie of southern France, before walking 780 km across the Pyrenees Mountains and through northern Spain to Santiago de Compostela.

It took years of research and self-discovery before Mary Magdalene gave me permission to go to sit in front of her relics. In 2023 I finally felt I was allowed to go to Provence, where her legend truly comes alive.

My mother and I travelled to France again in 2023, this time to walk in the footsteps of Mary Magdalene and hear the local legends of Provence.

What Happened to Mary Magdalene After the Crucifixion?

Following Jesus’ crucifixion, Mary Magdalene did not live out the rest of the her days in obscurity. Far from it. Despite the best efforts of the other disciples to ignore her existence, Mary Magdalene was inflamed by the mission Jesus had given her: to share the Good News.

Mary Magdalene understood this good news was not only for her but for all.

The problem was, there was a target on the backs of the followers of Jesus. People like Saul of Tarsus (who became St Paul) took it upon themselves to hunt down the followers of Jesus. Driven by his zeal for maintaining the Jewish faith and his view of Jesus’s teachings as heretical, Saul sought the approval of the high priest, acting on his own beliefs for his persecution.

Fearing for her life (and probably her children with Jesus), Mary Magdalene escaped Jerusalem to Gaul (France). In France legends describe Mary Magdalene arriving with a large entourage (about 74 people) south of Marseilles.

The town is now called Saintes-Maries de la Mer – Saint Marys of the Sea after ‘the Marys’ who accompanied Mary Magdalene – Mary Jacobe and Mary Salomé. The church of the Saintes-Maries de la Mer (St Marys of the Sea) hold treasures, including the hand reliquaries of the Marys.

The French legend says Mary Magdalene arrived in Gaul in 36 CE but the Church say 42 CE, when James the Just, the brother of Jesus, was martyred.

According to In ‘The Golden Legend’ Jacobus de Voragine (c.1260) wrote: “S. Maximin, Mary Magdalene, and Lazarus her brother, Martha her sister, Marcelle, chamberer of Martha, and S. Cedony who was born blind, and after enlumined of our Lord; all these together, and many other Christian men were taken of the miscreants and put in a ship in the sea, without any tackle or rudder, for to be drowned.”

Amongst her companions were her sister Martha, her brother Lazarus, Mother Mary’s sisters Mary Jacobe and Mary Salomé and Sara the Egyptian – called a servant – and Sidonius, who become bishop. They brought the relics of St Anne, Mother Mary’s mother, Jesus’ grandmother, with them.

This fresco depicts the arrival of the boat of Mary Magdalene and her companions in Marseille, XIV, by Giotto di Bondone (c.1320) from the Basilica of St Francis, Assisi, Italy.

According to legend, the exile party embarked from Alexandria, Egypt to begin their perilous journey. The boats at the time were not strong enough to travel across the Mediterranean. From evidence of Mary Magdalene and Lazarus in Malta and Cyprus they hugged the coast and stopped frequently for supplies.

Local legend of Provence claims that Mary Magdalene and her companions were put on a rudderless boat without a sail by the Romans to make them disappear without them becoming martyrs.

A more likely story is that the ship was one of a fleet of tin merchant Joseph of Arimathea, possibly Jesus’ uncle, who gave Jesus a cave tomb at short notice. Joseph of Arimathea was incredibly wealthy and more than capable of bringing many people from Alexandria in Egypt to France, including Mary Magdalene and her companions.

According to tradition, the exile party began to preach near the temples of the gods of the various pagan traditions in Massilia (Marseilles) at the time. Mary Magdalene is remembered in local legend as the greatest preacher of the teachings of Jesus known as the Way of Love in southern France. Here we have a painting of ‘Preche de la Madeleine in Marseilles’ from 1515.

Mary Magdalene and her companions were said to have been responsible for converting many in Gaul and were credited with bringing Christianity to Gaul.

Mary Magdalene preached and converted followers to the teachings of Jesus, known locally as the Way of Love. Lazarus went to Marseilles. Maximin was the first to come to Aix en Provence to evangelise with the youngest in the boat, Sidonius. Maximin is seen as the first leader (bishop) of Aix.

When my mother and I arrived in Provence, I was blown away by how real these legends were in the lives of the French. Before coming these legends had felt hard to prove, with little or no evidence to substantiate the claims. But arriving in Provence changed that for me…

Incredibly, the French have passed on the stories of these early missionaries. We went to the crypt where Mary Magdalene and Lazarus first took refuge in Marseilles.When Mary Magdalene and Lazarus arrived, they were fed by the kindness of locals, but they had to hide from the Romans to stay safe. They stayed in a crypt of a monastery, where they preached to anyone who would listen.

Incredibly, the French have passed on the stories of these early missionaries. We went to the crypt where Mary Magdalene and Lazarus first took refuge in Marseilles.When Mary Magdalene and Lazarus arrived, they were fed by the kindness of locals, but they had to hide from the Romans to stay safe. They stayed in a crypt of a monastery, where they preached to anyone who would listen.

I sat in what is known as “Lazarus’ Seat” where he sat to preach. It is incredible to be in the exact place where Lazarus and Mary Magdalene slept, ate and spoke the good news to the locals. We spent time where they had once slept. Carved into the stone was a face, thought to be Lazarus, along with various pagan symbols such as snakes and the Tree of Life. It is such a powerful experience to sit in the energy that lingers in these historic places.

Mary Magdalene is also believed to have travelled by boat along the Spanish coast to what is now known as Camino del Norte (the Way of the North) or Camino de la Costa (Coastal Way). In her book ‘Guardians of the Dragon Path: Ancient Temples of the Pyrenees, The Way of the Stars Camino, A Magdalena Meridian’ Ani Williams suggests Mary Magdalene might have carried the body of James the Great, son of Zebedee and Jesus’ disciple, also known as James, Son of Thunder, to Santiago de Compostela. I have not walked this Camino yet but it is on my bucket list.

This was so exciting to discover, considering the first trip to France had been combined with my mother’s desire to walk the Camino de Santiago, a 781km hike from the French side of the Pyrenees to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain. Christian pilgrims walked from all over Europe, usually for penance, knowing they would never return home, to pay their respects and ask favours of Santiago – St James. The Camino de Santiago also became an initiation route used by holy orders such as the Knights Templar, who guarded the route with castles scattered along its path.

The story goes that James was sent to evangelise Spain where he had converted many followers to Jesus. He returned to his homeland around 42 CE. In Jerusalem he was considered a threat and beheaded at the command of King Herod Agrippa in around 44 CE (Acts 12:1-2). Various sources describe his body being returned to Spain by unnamed followers of his by sea, landing at Padròn in Galicia and carried overland of Santiago de Compostela.

Ani Williams describes more than 94 churches to Mary Magdalene on the coastal Camino from Bidart to Santiago! When her ship stopped for supplies Mary Magdalene would preach to the people, leaving her legacy all along the Atlantic northern coastline of Spain. Ani Williams notes Mary Magdalene’s popularity continues to this day, with festivals on her feast days attended by thousands.

Ani Williams describes more than 94 churches to Mary Magdalene on the coastal Camino from Bidart to Santiago! When her ship stopped for supplies Mary Magdalene would preach to the people, leaving her legacy all along the Atlantic northern coastline of Spain. Ani Williams notes Mary Magdalene’s popularity continues to this day, with festivals on her feast days attended by thousands.

This image is the ‘Embarkation of the Body of St. James the Greater, Bound for Spain’, painted about 1425 by Master of Raigern.

When I visited the great cathedral in the medieval centre of Santiago de Compostela, I heard tales of an unnamed disciple who brought the body of St. James back to Spain. Now why would this disciple not be honoured and named? What did the Church have to hide?

There are another 64 churches to Mary Magdalene in Catalonia region, on another coastline in northeastern Spain. There is also evidence of Mary Magdalene in England. She certainly got around!

In Her Presence

In Provence, the locals believe Mary Magdalene was the same Mary as Mary of Bethany, the sister of Martha and Lazarus, all close friends of Jesus. The people of Provence and Languedoc believe Mary Magdalene was the beloved companion of Jesus.

We walked through an ancient grove sacred to Artemis and up the mount to the cave known as La St Baume where legend claims Mary Magdalene spent the last 33 years of her life in contemplative prayer. It is most likely a story to confuse the legends of Mary Magdalene evangelising the whole of France – she was far too busy to be hidden in a cave for 33 years! But she most likely prepared for her death here, spending her last days meditating before she died.

The cave where Mary Magdalene stayed is now covered over by a kind of chapel, with stairs, crosses, statues other Christian additions fitted in around the natural cave walls and ceiling.

The cave where Mary Magdalene stayed is now covered over by a kind of chapel, with stairs, crosses, statues other Christian additions fitted in around the natural cave walls and ceiling.

We arrived while a service was taking place. I found it distracting and disconcerting. The Dominican monks who preside over the chapel happen to be the same order who hunted down the Mary Magdalene followers, the Cathars, after the Albigensian Crusade, in the Inquisition (as the inquisitors!) then when they started to run out of Cathars they moved their attention to any heretics, including witches. But we will get to that soon…

In ‘The Golden Legend’ Jacobus writes that on the last day of her life, Mary Magdalene sent a hermit to ask Maximin, now the bishop of Aix, to come to her and give her the Eucharist. She wanted to be with Maximin in her last moment. Her brother, Lazarus was already dead.

Maximin was described as her closest companion after Jesus in her last years in France. Mary cried tears of joy and, after taking it, she lay down and died. A pillar marks where she died and ascended. Her body was taken to be buried by Maximin, who was later buried beside her. The date was July 22 (her feast day) around the year 72 CE.

The date of Mary Magdalene’s death was recorded in the Vatican Desposnyi genealogy presented to Pope Sylvester III in 318 CE and is in the Vatican archives. She was sixty years old.

The most special day was at Basilica St Maximin where the relics of Mary Magdalene are held in a gold reliquary in the crypt. This photo is inside the main cathedral before going down a steep flight on stone steps into a small room where her skull is housed in a gold reliquary behind an iron gate.

The most special day was at Basilica St Maximin where the relics of Mary Magdalene are held in a gold reliquary in the crypt. This photo is inside the main cathedral before going down a steep flight on stone steps into a small room where her skull is housed in a gold reliquary behind an iron gate.

Sitting in the presence of Mary Magdalene was a profoundly moving experience for me. The whole of the Basilica St Maximin was pulsing with her energy. We entered the crypt and approached the gate in small numbers as it was a tiny room.

I sat on the last step to connect with Mary Magdalene and basked in her presence. I would describe it like sitting in front of a furnace! Even though I sat on the bottom step a few meters away, I was being blasted by the energy pouring out of her skull.

I was overwhelmed by feelings. Mary Magdalene didn’t say much but I was filled with her energy. I offered her gratitude, love and awe. I made requests for her to accompany and guide me.

I was overwhelmed by feelings. Mary Magdalene didn’t say much but I was filled with her energy. I offered her gratitude, love and awe. I made requests for her to accompany and guide me.

When I finally felt ready to make my way out of the crypt, I discovered I’d been down there for 30min. I was buzzing, vibrating, unable to quite enter the world again so I sat on a bench in the sun for a while to adjust and anchor the energy I had received.

Why Isn’t This Common Knowledge?

Back in 2018, my research kept directing me away from Mary Magdalene and towards the Cathars of the Languedoc region of southern France. I was drawn inland to research the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains.

Back in 2018, my research kept directing me away from Mary Magdalene and towards the Cathars of the Languedoc region of southern France. I was drawn inland to research the foothills of the Pyrenees Mountains.

The more I learned about this tiny pocket of France the more I discovered about a secret legacy that Mary Magdalene had left. I discovered that the Cathars of the Languedoc were a branch of Christianity ruthlessly suppressed in the thirteenth century. authority.

This painting is from Scenes from the Life of Mary Magdalene with Mary Magdalene and Cardinal Pontano by Giotto di Bondone in the Basilica inferiore di San Francesco d’Assisi.

I began to uncover the true history of a Christian female spiritual lineage and to reconnect with my own natural spiritual

In the 1200s the Catholic Church sent the first and only crusade against Christians into France. Known as the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229), the crusade attempted to destroy a Christian sect, the Cathars.

The crusaders demanded each town to expel their Cathars. On July 21–22, 1209, Mary Magdalene’s feast day, in Beziers a papal legate, the abbot of Cîteaux, demanded the delivery of 222 heretics. When the demand was refused, the abbot declared, “Slaughter them all!” He added, “God will know his own”. 20,000 residents were massacred, many sheltering inside the Catholic church.

Called Cathars or Albanenses by the Catholic Church after the white robes they wore, the word Cathar means pure and Albanenses comes from the Latin word alba which means white. Among the people of the Languedoc, they were not called Cathars but simply Bonnes Hommes and Bonnes Femmes – Good Men and Good Women. Among themselves they spoke of each other as Friends of God.

This medieval manuscript illustration showing Pope Innocent III (c. 1198-1216 CE) and the crusaders of the Albigensian Crusade in southern France (1209-1229 CE) from the Chronicles of Saint-Denis, British Library, London. The Cathars were pacifist, making them an easy target. The Kingdom of Aragon and the nobility of southern France, including the Count of Toulouse, provided aid to the Cathars. Many of the local Knights Templar came to their aid, but this only made them a target too.

The Cathars were spiritual adepts and seers, shamanic practitioners and healers, and initiates in the tradition of the death and rebirth mysteries.

Their aim was to put each man in touch with his own inner spirit, to help him learn to trust that inner guidance rather than any outer authority. The Cathars were considered a heretical group that did not believe in the doctrines, teachings, and authority of the patriarchal Church and its hierarchies at Rome. They were appalled by its corruption and wealth.

The crusade sought to exterminate the Cathar people for the crime honouring Mary Magdalene. The Cather Church of the Holy Spirit stressed was not doctrine but following the actual teaching of Jesus that had been passed down through the centuries from the time of the Apostles.

The crusade sought to exterminate the Cathar people for the crime honouring Mary Magdalene. The Cather Church of the Holy Spirit stressed was not doctrine but following the actual teaching of Jesus that had been passed down through the centuries from the time of the Apostles.

The Cathars rejected the church concept of the virgin birth as well as the belief that Jesus was the Son of God and his bodily resurrection, going against the Nicene Creed.

This Folio of the Pentecost from 1386, is housed in the Getty Museum.

The Cathars did not believe that Jesus died on the cross in his physical body to redeem the sins of humanity. The Cathars believed Jesus was a great teacher who came to save people from ignorance or unconsciousness, not sin. So the Cathars did not believe in original sin. They did not believe in the idea of hell and purgatory. This removed the fear of death that was part of Catholic indoctrination.

This religion emphasised release from prison, enlightenment, spiritual growth and service. The Cathars believed the world was imperfect because of human enslavement to the power of the Demiurge, not because of original sin. They believed the Catholic Church had withheld knowledge of ourselves as repositories of the hidden light of the Holy Spirit and barred their access to the true teaching of Christ.

This religion emphasised release from prison, enlightenment, spiritual growth and service. The Cathars believed the world was imperfect because of human enslavement to the power of the Demiurge, not because of original sin. They believed the Catholic Church had withheld knowledge of ourselves as repositories of the hidden light of the Holy Spirit and barred their access to the true teaching of Christ.

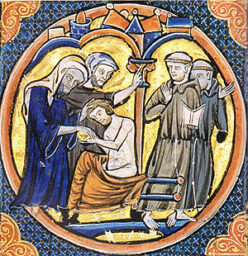

This image from a Medallion in a Bible depicts Franciscan Friars witnessing the heresy of a Cathar Consolamentum – a unique sacrament or ritual performed when death was imminent. Dated from the second half of the thirteenth century, now housed in the Bibliothèque nationale de France.

No wonder the Cathars were targeted by the Catholic Church. But there is more. The Cathars did not worship Jesus and they found worshipping the object of his torture – the cross – obscene and grotesque. The Cathars believed in becoming Jesus, understanding Jesus taught The Way.

Instead of the Christian cross, the Cathars used a dove or a X, an oblique cross, as emblematic of the Gnostic Mary Magdalene tradition. This represented a signature for a mystery called Bridal Chamber, a mystery described in the Gospel of Philip, a gnostic apocryphal text from the third century.

Mary Magdalene was cancelled. If the Church did not acknowledge her contribution, if they could destroy the evidence, they might be able to continue to deny the importance of women in Jesus’ ministry.

Mary Magdalene was cancelled. If the Church did not acknowledge her contribution, if they could destroy the evidence, they might be able to continue to deny the importance of women in Jesus’ ministry.

This is from a manuscript decoration XVº from ‘Speculum historiale’ ‘The Mirror of History’ by Vincent of Beauvais (c.1184/1194 – c.1264) a Dominican friar at the Cistercian monastery of Royamont Abbey, France.

In the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in the year 325 CE, when the word Cathari was used. This is quoted in Philip Schaff and Henry Wace in ‘Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers’, (Second Series, vol. 14: I Nice AD 325 Canons of the Council of Nicaea), translated by Henry R. Percival: “If those called Cathari come over [to the faith], let them first make profession that they are willing to communicate [share full communion] with the twice-married, and grant pardon to those who have lapsed…” (Canon 8 of the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea).

This also tells us that the Cathars did not recognise second marriages and did not believe in penance as forgiveness of sins after baptism, views that differed from the Orthodox Church.

Why is this important?

The Cathars themselves claimed their teachings came directly from Jesus through Mary Magdalene and the legacy of their descendants. They claimed that their teaching was descended directly from that of the Apostles and the early Church and had nothing to do with the Church of Rome. They claimed their church was as old as Rome.

The Cathars believed Jesus was not the Son of God but a great teacher like an elder brother of humanity who had come to rescue souls imprisoned in the world, ignorant of their origin and destination. They taught that Christ was the indwelling divine spirit in man, the light shining in darkness.

They believed that Mary Magdalene was the companion and beloved of Jesus in the higher realms. The Cathars acknowledged Mary Magdalene in the spread of early Christianity. Their most sacred text was the ‘Book of Love’, along with the Knights Templar. This text was the cornerstone of the teachings offered by Mary Magdalene in order to become perfect.

This Pentecost image is from the sixth century with Mary, the apostles and the Holy Spirit represented as a dove from the Rabula Gospels Folio (Florence, Biblioteca Mediceo Laurenziana, cod. Plut. I, 560 CE).

This Pentecost image is from the sixth century with Mary, the apostles and the Holy Spirit represented as a dove from the Rabula Gospels Folio (Florence, Biblioteca Mediceo Laurenziana, cod. Plut. I, 560 CE).

Mary Magdalene’s divinity is represented by the dove, symbolising the Holy Spirit. She is often portrayed similar to Jesus, possibly implying that she was his feminine counterpart and successor, who possessed similar spiritual wisdom and power.

This hand gesture Mary Magdalene uses, with the first two fingers and thumb extended, is a sign of benediction. This hand gesture Mary Magdalene uses, with the first two fingers and thumb extended, is a sign of benediction. This mudra was reserved for Jesus in the iconography in Christian art to signify Jesus’ power to bless and heal.

Unlike the Orthodox Church, with no woman priestesses, the Gnostic Christian tradition viewed Mary Magdalene as the embodiment of feminine aspect of God and worshipped her with commitment and intensity instead of Christ. Mary Magdalene was venerated as Sophia, the personification of the Wisdom aspect of God.

Mary Magdalene’s role as a teacher contributed to the Cathar belief that women could serve as spiritual leaders. Women were included in the Perfecti in significant numbers, with numerous receiving the consolamentum after being widowed or choosing to leave their husbands in middle age.

Catharism embodied the original teachings of Jesus: a message of love, enlightenment and relationship with the divine ground. Catharism flourished where the Way was first taught by Mary Magdalene. As recipients of his teaching, the Cathars knew Jesus’ work was to be emulated as a blueprint for the evolution of the soul.

Catharism embodied the original teachings of Jesus: a message of love, enlightenment and relationship with the divine ground. Catharism flourished where the Way was first taught by Mary Magdalene. As recipients of his teaching, the Cathars knew Jesus’ work was to be emulated as a blueprint for the evolution of the soul.

This image is from the Ingeborg Psalter, Manuscript (Ms. 9), from around 1195, housed in the Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

The Church did not want anyone left alive who knew of the ‘Book of Love’ and its explosive content. The ‘Book of Love’ was sought throughout the Languedoc in the bloody Albigensian Crusade to wipe the Cathars out. But it is believed it was never found. It was smuggled out of Montségur two days leading up to the fall. But no one knows for sure.

The Church was determined to deny Mary Magdalene’s importance and hid so much of the actual historic events. While the crusade massacred town after town, they burned and destroyed evidence of Mary Magdalene’s presence in France. But the French never forgot.

The Cathar faith thrived alongside the Knights Templars in Languedoc. When they were hounded out of extinction, secret societies sprang up throughout Europe to hold this alternate version of the story for perpetuity.

The secret spread through Europe, birthing compositions like Madonna della Misericordia by Lippo Memmi (1291-1356) from the Chapel of the Corporal Duomo, Orvieto, Italy. Here Mary Magdalene dwarfs the devotees seeking her presence above and beneath her extended cloak.

The message is clear: her devotees were many. Mary Magdalene is viewed as leading an exemplar Christian life, more fierce and faithful than penitent, who had her own disciples, preached on an Apostolic mission in Provence, converted communities and performed miracles of healing.

A Guide For Our Times

![]() Mary Magdalene is making herself known. Mary Magdalene is returning now stronger than ever, laying her claim as a mystic visionary and wise teacher of the Way of Love, as taught by her and Jesus. The Divine Feminine face of God is returning to the collective consciousness.

Mary Magdalene is making herself known. Mary Magdalene is returning now stronger than ever, laying her claim as a mystic visionary and wise teacher of the Way of Love, as taught by her and Jesus. The Divine Feminine face of God is returning to the collective consciousness.

I am amongst thousands of women who have had a vision of Mary Magdalene. These visions seem to be increasing with more and more women drawn to investigate her and celebrate her.

This image of ‘Mary Magdalene as one of the Myrrhbearers’ has the words “Christ is Risen” in Greek at the top, depicting her discovery of the empty tomb. She holds her jar of anointing oil, hand on the lid, offering its secrets for those with ears to hear and eyes to see…

But that’s a story for another day.