Mary Magdalene, the Mystic

In all the contention of who Mary Magdalene was the focus is often on her relationship with Jesus rather than the truth of who she was. I personally believe Mary Magdalene was most likely an ordained priestess, a prophetess, a mystic, a powerful preacher and an initiator who performed baptisms. Mary Magdalene continued her own ministry after the crucifixion who preached Jesus’ message in Gaul (France) and Spain.

I’m not just making this up – there is proof!

This whispers of her training as an ordained priestess with years of experience and secret initiations. Mary Magdalene was wealthy, educated and accomplished in speaking.

Ancient Prophetesses

Before we look at the proof that Mary Magdalene was a mystic and prophetess we need to see her within the context of her culture. Were there precedents? Were there other women singled out as mystics or prophetesses in Jewish religion?

Why, yes! Yes there were!

Ani Williams in her book ‘Guardians of the Dragon Path: Ancient Temples of the Pyrenees, The Way of the Stars Camino, A Magdalena Meridian’ states that “The creative power of the word or song, as it manifested through their voices, was well known by the Bath Kol. These holy women were considered as aspects of the Shekinah, ‘Divine Presence’ the Ruach Ha Kodesh, ‘Holy Spirit’, and their prophetic state was precipitated by sacred music and singing holy names.”

The Torah uses the words prophet and seer interchangeably. A seer used divinatory techniques such as reading animal entrails to foretell the future.

In the Zohar the Bat Kol (also spelled Bath Kol) were described as “the voice of many waters, and like the voice of loud thunder” who “sang a song descended from heaven. Their oracular messages served as guidance for the people and their wisdom was a mediation between the Holy Spirit and Earth”.

In the Zohar the Bat Kol (also spelled Bath Kol) were described as “the voice of many waters, and like the voice of loud thunder” who “sang a song descended from heaven. Their oracular messages served as guidance for the people and their wisdom was a mediation between the Holy Spirit and Earth”.

Ani Williams explains “The tradition of singing the sacred names would have been maintained by the entire extended family of exiles from Palestine.”

What I find exciting is that there were seven prophetesses and priestesses named in the Old Testament: Sarah, Miriam, Deborah, Hannah, Abigail, Huldah and Esther. Five prophetesses are named in the Torah: Miriam, Deborah, Huldah, Noadiah and an unnamed woman who has a son with Isiah.

In ‘The Hebrew Priestess: Ancient and New Visions of Jewish Women’s Spiritual Leadership’ Jill Hammer explains that “Like the prophets of ancient Israel, the prophetesses have a relationship not only to ritual but to ethics. Deborah counsels courage, Miriam decries the abuse of power and Huldah affirms Deuteronomic morality. All three women also have something of the warrior in them – each one celebrates victory or counsels the overthrow of an enemy.”

In Israelite myth and legend, Moses was never called a prophet. His sister Miriam was. Miriam “was one of the three leaders of the Israelite nation in the wilderness: “I brought you up out of Egypt and redeemed you from the land of slavery. I sent Moses to lead you, also Aaron and Miriam” (Micah 6:4).

The Book of Jasher (mentioned in Joshua 10:12-13; 2 Samuel 1:18-27) paints Miriam in an even greater light. This book was believed lost until it appeared in England in 1720. In Jasher 12-15 Miriam is portrayed as a prophetess of such great standing she even eclipses her brother Moses.

This portrayal of Miriam as a great prophetess is echoed in the Talmud where was the only woman equal to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Aaron and even Moses. The Arabic word kahim cognate to kohen/kohenet means both priest and diviner – and in ancient Israel prophecy was a very important aspect of the power of the priesthood.

The high priest of Israel carried the urim and tummin, divination tools, inside the sacred breastplate, and Moses and Samuel are depicted as serving in both prophetic and priestly roles. It was Miriam, not Moses, who found water in the desert. Later, rabbinic legend depicted Miriam as the source of a mysterious moving well of water that sustained the people in the wilderness (Babylonian Talmud, Taanit 9a; Numbers Rabbah 1:2; Song of Songs Rabbah 4:14).

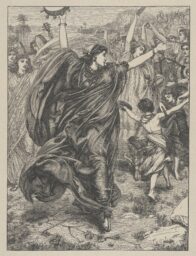

This wood engraving on India paper depicts Miriam and the Israelites celebrating their victory over Pharaoh and his army, by the Dalziels (Dalziels’ Bible Gallery) (1881), after a painting by Sir Edward John Poynter (1864), now housed in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Book of Jasher (who was the personal staff-bearer to Moses) tells us the story of the Exodus, but from a different perspective. It says that it was not Moses but Miriam who was the spiritual leader of the tribes. The Hebrew people were yet to worship the Hebrew God, but Asherah, who was symbolised as a golden cow. Miriam may have served in a similar role as a patron or ancestor for Levite women who later served in priestly functions (Deuteronomy 26:14).

The Book of Jasher (who was the personal staff-bearer to Moses) tells us the story of the Exodus, but from a different perspective. It says that it was not Moses but Miriam who was the spiritual leader of the tribes. The Hebrew people were yet to worship the Hebrew God, but Asherah, who was symbolised as a golden cow. Miriam may have served in a similar role as a patron or ancestor for Levite women who later served in priestly functions (Deuteronomy 26:14).

Jill Hammer explains “Judges were charismatic military leaders and governors, inspired by God to preserve the Israelite tribes. Deborah was described as both judge and prophet. The palm tree of Deborah is probably a shrine or pilgrimage location – the people ‘went up’ to her, and the verb is the same as ‘to go on pilgrimage’. Since the location of her tree is so carefully given, Deborah is probably a known and respected shrine priestess who gives oracles to those who come to request them of her.”

Deborah, whose name means bee, may have connections with the melissae priestesses of Greek and Minoan culture. Deborah sat under a palm tree, the sacred tree of the Canaanite goddess Asherah. The Hebrew word for bee is related to shrine (devir) and word (davar), making it likely Deborah was a dispenser of words (devarim) at the shrine (devir).

Both Miriam and Deborah were both described as prophetesses and prophets, Deborah was a judge, or more accurately a leader, who sat under a date palm tree in the hill country dispensing advice and judgments to all who came to her. Mentioning a palm tree was short hand for a devotee of Asherah (for more on Asherah see blog: ‘Goddesses of Canaan’ and ‘Goddesses of Judaism’).

Both Miriam and Deborah were both described as prophetesses and prophets, Deborah was a judge, or more accurately a leader, who sat under a date palm tree in the hill country dispensing advice and judgments to all who came to her. Mentioning a palm tree was short hand for a devotee of Asherah (for more on Asherah see blog: ‘Goddesses of Canaan’ and ‘Goddesses of Judaism’).

It was a struggle for Moses to wean his people away from the worship of Asherah and he had to resort to imprisoning Miriam, yet it still took hundreds of years during which time Yahweh and Asherah were worshipped together, before the priests were able to stop the worship of the goddess. These officials may have been priests, prophets or prophetesses, neviah.

That means the Asherah prophet priestesshood is as old as Moses.

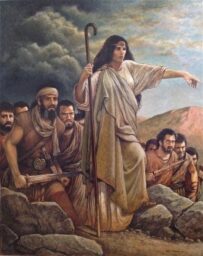

This is ‘Miriam the prophetess’ by Anselm Feuerbach, 1862.

Deborah was an oracle and spokesperson for the Hebrew God, offering wise advice to anyone who sits before her. She may have used divination but has not survived. In her wise crone aspect, Asherah also counselled the ruling god and stood as a mediator between her husband and the other gods.

Asherah and her cult was primarily about the roles women played to bring abundance and fertility to the family and to hold families together. As Asherah’s earthly manifestation, Deborah was the Mother of Israel who protected, nurtured and liberated her people.

In this role, Deborah cared enough to do whatever it takes as any mama bear will do to protect her young, including berating kings and generals and leading armies into battle!

We can presume Miriam held this similar position as the physical, earthly representative of the goddess Asherah in her wise crone aspect in her own time. One of the roles reserved for women was to observe rituals for preparation for war, defeat and victory.

We can presume Miriam held this similar position as the physical, earthly representative of the goddess Asherah in her wise crone aspect in her own time. One of the roles reserved for women was to observe rituals for preparation for war, defeat and victory.

One of these roles was a performance of songs and dances. Dance has also been a way for women to express their sensuality and power. Both Miriam and Deborah led the women in jubilant victory dances.

In Exodus it is Miriam who leads the women to sing the last part of the Song of the Sea to celebrate the Israelites escaping the pharaoh’s army. I imagine Miriam’s head thrown back in jubilation, swinging her hips, dancing towards the spent Israelites, arms held above her head tapping and twisting her tambourine as she let out her ululations.

In the ancient world women were more susceptible to possession by good or bad spirits than men because a female body had more openings. This meant that being filled with a spirit and speaking, that is being a woman prophet, was linked with sexual purity or impurity.

The image is ‘Songs of Joy’ by James Tissot from around 1896-1902.

In ‘Resurrecting Mary Magdalene: Legends, Apocrypha, and the Christian Testament’ Jane Schaberg states: “The pattern is a common one: the powerful woman disempowered, remembered as a whore or whorish.” If a woman prophet became too powerful she was often insulted and accused of being a whore or a harlot. These women were dragged unceremoniously from their high standing and diminished.

Jezebel (1 Kings 18-21; 2 Kings 9) is described as having painted eyes and head adornments 2 Kings 9:30) before being thrown from her high window and eaten by dogs. The Samaritan woman had multiple relationships (John 4) and the prophet of Thyatira “that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet…[and] refuses to repent of her fornication” (Revelations 2:20-23).

Jezebel (1 Kings 18-21; 2 Kings 9) is described as having painted eyes and head adornments 2 Kings 9:30) before being thrown from her high window and eaten by dogs. The Samaritan woman had multiple relationships (John 4) and the prophet of Thyatira “that woman Jezebel, who calls herself a prophet…[and] refuses to repent of her fornication” (Revelations 2:20-23).

This is ‘Jezebel, The Heathen Queen’, artist unknown, dated 1874.

Everything went well so long as the prophetess did not challenge the masculine right to authority. Moses’ sister the prophet Miriam (Numbers 12) was brave enough to argue with her brother and challenge Moses’ claim to being God’s spokesman. In return, Miriam was not praised for her wisdom in tempering his movements.

Instead, Miram was unceremoniously demoted and died in obscurity. In Jasher leprosy is never mentioned. Instead, Miriam is punished by her brother Moses who placed her under house arrest for political expediency. But he is forced to release her when Miriam’s supporters rally to her defence.

Jane Schaberg explains:“The sages of the Talmud (200-600 CE) believed that the age of prophecy had come to an end…The sages believed that the bat kol was the last remnant of the prophetic gift.” (Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 9a). In the story of King Solomon, judging between two mothers (one holding a dead baby, one a living baby) to decide who is the mother of the living baby. In the version of this story in the Talmud Solomon is not the one to declare who the mother is, “a bat kol went forth and said: ‘She is the mother’.” (Babylonian Talmud, Makot 23b).

Jane Schaberg states:“Bat kol appears as the voice of personal information, of prophecy within embodied human experience. Solomon knows which woman is the child’s mother, even if he cannot prove it. The bat kol inspires Solomon’s own words (“She is his mother”) as if the Divine Presence Herself, denied the power of speech, must speak through the mouths of humans to express prophetic truth. In this story, the bat kol is a kind of prophetess, providing a human voice with her own words.

Mary Magdalene, the Mystic

During Mary Magdalene’s lifetime there was the order of Bat Kol, Daughters of Voice. These were prophetesses for the wisdom of heaven. “The Hebrew Soncino Zohar defines garon [meaning throat] as the vehicle for the creative word, infused with pure intention, and states that the glory of the holy passes through it: ‘… through which perennially flows the mystic force of the “spirit of life”’.” (Soncino Zohar, Bereshith, 74a).

During Mary Magdalene’s lifetime there was the order of Bat Kol, Daughters of Voice. These were prophetesses for the wisdom of heaven. “The Hebrew Soncino Zohar defines garon [meaning throat] as the vehicle for the creative word, infused with pure intention, and states that the glory of the holy passes through it: ‘… through which perennially flows the mystic force of the “spirit of life”’.” (Soncino Zohar, Bereshith, 74a).

In Gnostic texts like the Gospel of Mary, Gospel of Philip, and Pistis Sophia, Mary Magdalene is portrayed as a spiritual teacher and initiatrix, someone who understood the teachings of Jesus on a deeper, inner level.

In the ‘Pistis Sophia’ Mary Magdalene expresses herself as a Bat Kol, a Sophianic Voice of wisdom with a depth of comprehension the male disciples cannot reach. As a result, the disciples complain and attempt to shut Mary Magdalene down, asking Jesus to stop her from speaking so they can have a chance.

Several of the traits Mary Magdalene demonstrates in the gnostic texts banned by the Orthodox Church are characteristics of a prophet or an apocalyptic seer. These include Mary Magdalene’s prominence, bold speech, leadership role, visionary experience (sometimes involving spiritual journey) and conflict.

This image is of Mary Magdalene contemplating. She holds a cross or crucifix while other icons are arranged around her, including a skull, prayer beads, and an open book. The artist has even added a jar of ointment just to be sure we don’t misunderstand who she is. (For more on the symbolism of the book see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene and Sacred Union’ or on the skull see my blog: ‘What’s With the Skull, Mary Magdalene?’).

I saw this large painting in the museum of sacred art, the Church of the Benedictines, in the Mosteiro de San Paio de Antealtares, Santiago de Compostela, Spain.

Mary Magdalene spoke boldly, was a visionary, and she was praised for her understanding. In Pistis Sophia Jesus spoke, saying “Miriam, thou blessed one, whom I will complete in all the mysteries of the height, speak openly.”

Jesus stated that “Mary Magdalene and John the Virgin will surpass all my disciples and all men who shall receive mysteries in the Ineffable.” Jesus was obviously impressed by her insightful answers “because she had completely become pure Spirit.”

In ‘Pistis Sophia’, Jesus praised her boldness and her superior understanding: “Mary [Magdalene] thou blessed one, whom I will perfect in all the mysteries of those of the height, discourse in openness, thou, whose heart is raised to the kingdom of heaven more than all thy brethren.”

In the ‘Pistis Sophia’ Mary Magdalene expresses herself as a Bat Kol, Daughters of Voice. A Bat Kol was a Hebrew Sophianic voice of wisdom. Mary Magdalene had a depth of comprehension the male disciples could not reach.

In the ‘Pistis Sophia’ Mary Magdalene expresses herself as a Bat Kol, Daughters of Voice. A Bat Kol was a Hebrew Sophianic voice of wisdom. Mary Magdalene had a depth of comprehension the male disciples could not reach.

In ‘Pistis Sophia’, Jesus praised her boldness and her superior understanding: “Mary [Magdalene] thou blessed one, whom I will perfect in all the mysteries of those of the height, discourse in openness, thou, whose heart is raised to the kingdom of heaven more than all thy brethren.”

In ‘Pistis Sophia’, Jesus described her as “she whose heart is more directed to the Reign of Heaven than all your brothers” and “blessed beyond all women on earth, because [she] shall be the pleroma of all pleromas and the completion of all completions.”

According to Gnostic belief, the pleroma (from the Greek word for fullness) is the plane below the Spiritual Plane or Treasury of the Light, which corresponds to the plane of abstract or superior mind. In ‘Pistis Sophia’, the pleroma is the realm where souls find bliss after liberation from the physical world. It is also connected to the concept of fullness or totality of divine powers.

This mixed media work called ‘Magdalena’ is by Lisbeth Cheever-Gessaman (She who Is).

In the ‘Gospel of Mary’ rather than offer parables, Mary Magdalene speaks from experience. She offers the disciples the fruits of her practice: her deep inner wisdom and knowing.

In the ‘The Gospel of Mary’ Mary Magdalene offers a vision that she was given by Jesus. She describes: “I had a vision of the Teacher, and I said to him ‘Lord, I see you now in this vision.’ And the Lord answered: ‘You are blessed, for the sight of me does not disturb you’.” (‘The Gospel of Mary Magdalene’ translated by Jean-Yve Leloup).

In the ‘The Gospel of Mary’ Mary Magdalene offers a vision that she was given by Jesus. She describes: “I had a vision of the Teacher, and I said to him ‘Lord, I see you now in this vision.’ And the Lord answered: ‘You are blessed, for the sight of me does not disturb you’.” (‘The Gospel of Mary Magdalene’ translated by Jean-Yve Leloup).

The vision is incredible in its detail and symbolism. It made me think of Inanna’s Descent into the Underworld passing through gates where she must relinquish parts of her identity, only Mary’s vision is of a tree that she ascends, relinquishing vices that sound very similar to the seven deadly sins.

Mary Magdalene was a mystic, a psychic, who could pass effortlessly between the veils. Mary Magdalene is the one who sees, who has the gift of seeing subtle dimensions beyond normal reality.

Magdalene with the Smoking Flame (c. 1640) by Georges de La Tour with her hand placed intimately on the skull resting in her lap. (For more on the skull ‘Mary Magdalene and the Skull’).

In the ‘The Gospel of Mary’ Mary Magdalene asked Jesus to explain the way she and others see him in visions, asking whether it is through the soul, psyche, or spirit, pneuma. He responds that it is not through either but through nous, the intelligence between the two, the bridge beyond personality and individuality. This is within a unified field beyond the separation of you or I, where true union occurs. Jesus explains “There where is the nous, lies the treasure.”

The Dialogue of the Saviour is a very damaged fragment of a text describing Mary Magdalene, Judas, Matthew, and Jesus conversing. This text from Nag Hammadi is the only existing copy, written in Coptic around 150 CE. The textual style resembles other Gnostic dialogues, such as the Gospel of Thomas, but it lacks cohesion and may be a combination of at least four different written sources.

In ‘Dialogue of the Saviour’ Mary Magdalene experienced visions and shared them with the others. At one point Mary Magdalene and the others see the resurrected Jesus being surrounded by light that stretched from heaven to earth. Jesus rose up this column of light. The next day at the ninth hour the heavens opened, and Jesus descended down a column of light.

In ‘Dialogue of the Saviour’ Mary Magdalene experienced visions and shared them with the others. At one point Mary Magdalene and the others see the resurrected Jesus being surrounded by light that stretched from heaven to earth. Jesus rose up this column of light. The next day at the ninth hour the heavens opened, and Jesus descended down a column of light.

At another point, Mary Magdalene is described staring into space for an hour before speaking. She interprets Jesus’ defeat of the powers of the world in her own words. For anyone who has had a vision, being able to put it into words and having the courage to share them is no mean feat.

This ‘St Mary Magdalene’ is by Timoteo Viti (1467-1524) housed in Venice, Doge’s Palace. She stands in what looks like a cave entrance, hands clasped together in front of her in a sign of prayer and humility.

In ‘Dialogue of the Saviour’ Mary Magdalene is portrayed as a woman who understands everything and has insights into spiritual matters. Mary attributes three aphorisms to Jesus: “The wickedness of each day [is sufficient], Workers deserve their food, Disciples resemble their teachers”. Mary speaks of the mystery of truth and their taking a stand in it. Jesus emphasises stripping oneself of transient things and following the path of truth to achieve spiritual purity.

The ending of ‘Dialogue of the Saviour’ describes the dissolution of “the works of womanhood,” which is interpreted as the end of fleshly existence and a return to the light. The text, however, is not misogynistic, and it presents Mary Magdalene as the disciple who best understands Jesus’ teaching. Its negative view of the “works of woman” apparently refers to its teaching that procreation and sex must be avoided in order to escape the cycle of birth-death-and-rebirth and finally enter the bliss of the “Eternal Existent.”

Ani Williams explains that “we can assume that Magdalena and her companions maintained this tradition as Daughters of Voice, giving them strength and clarity on their long voyages. Maria Magdalena, as one of the likely practitioners of the Bath Kol tradition…”

Mary Magdalene was possessed of demons – she had spirits inside her. She could see visions and receive messages. She could see the resurrected Jesus and had visions of him afterwards. She was most definitely a prophetess.

Feature Image: ‘Mary Magdalene in the Cave’ by Hugues Merle