The Goddesses of Canaan

Canaan was an ancient Semitic-speaking civilization in the southern Levant during the late second millennium BCE. The southern Levant refers to an area encompassed by modern Israel, Lebanon, Jordan, parts of Syria and Palestine.

Canaan is the ancient name of this region, and a Canaanite culture was prominent until the Iron Age, when the kingdoms of Israel and Judah dominated. Trade between Canaan and Egypt had been well established since at least 3300 BCE. From the late Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1600 BCE) onwards, Canaan was under Egyptian rule.

Canaan was populated by Midianites, semi-nomadic camel traders of the Sinai Peninsula, Serite copper miners of the Gulf of Aqaba, Phoenician sea-traders of the Levantine coast (Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, Arwad and Acre) and agricultural Canaanites inland. Canaanite civilization even extended onto northern Egypt where it merged with Egyptian religion in the Nile delta. If you aren’t familiar with the ancient goddesses it is worth reading my blogs: The Goddesses of Egypt and The Goddesses of Mesopotamia.

Using archaeological evidence, we now know that Canaanite language, culture and religion spanned a wide region from Ugarit in the north to Sinai in the south. The cities of Ugarit, Tyre, Sidon, Byblos and Arwad were thriving ports.

From the Late Bronze Age Amarna Period (fourteenth century BCE) Canaan became significantly important as the convergence point of the Egyptian, Hittite, Mitanni, and Assyrian Empires. Canaan was the major trade route between the Mediterranean countries of Italy and Greece, the Persian Gulf and a vital corridor between Egypt and Mesopotamia.

In 1928, a farmer opened an old tomb while ploughing a field in northern Syria (modern Ras Shamra). This happy accident helped archaeologists discover This was the fabled northern Assyrian provincial capital Ugarit located in the nearby seaport of Minet el-Beida. To the south was Jericho on the trade route overlooking the deserts to south and west, with the Jordan Valley to the east.

Excavations in Ugarit have revealed a city with a prehistory reaching back to about 6000 BCE. Ugarit was a thriving Canaanite city-state in the Late Bronze Age (c.1550-1200 BCE) boasting a population of between 7,000-8,000 until its destruction either by Sea Peoples or civil war. The kingdom was one of the many that fell during the Bronze Age Collapse.

Claude Schaeffer, co-director of the first excavation at Ugarit in 1939, noted the high status of women in ancient Ugarit society. Ugarit records state that a divorced or widowed woman kept her own property. Husbands left their property to their wives not their children. Children were told not to argue with their mothers but to respect and obey them.

Interestingly, there are far more female figurines and images than there are male ones. Use of figurines continued in Jerusalem throughout the Late Iron Age. In Canaan, 90% of Iron Age votive figures are female.

Archaeologists have uncovered many Iron Age female talismans in Canaan, while male figures are non-existent. Full-scale destruction of southern cities attempted to wipe out evidence of goddess worship, meaning less archaeological finds in the region.

However, archaeological finds in northern Canaan and neighbouring lands in close contact with the Hebrews have given scholars proof of widespread goddess worship and demonstrate that genocide had occurred in some areas, erasing all trace.

This suggests deeply entrenched feminine values in Canaanite culture. In an article ‘9,000-year-old Neolithic City Discovered in Jerusalem Valley’ Ruth Schuster and Nir Hasson describe recent archaeological discoveries at Motza are compared with similar finds from Hazeva and Qitmitm stands, shrines and altars from Megiddo, Taanach and Beit Sh’ean.

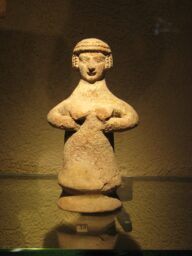

The artefacts from these sites give a significantly deeper understanding of religious life in ancient Canaan, with the discovery of figurines of females in various positions and states of dress, dogs, horses and bulls. These figurines suggest multiple deities were once worshipped. This figurine is from Reuben and Edith Hecht Museum, Haifa, Israel.

Canaanite goddesses most likely originally came from Mesopotamia. In ‘Journey of the Priestess: The Priestess Traditions of the Ancient World: A Journey of Spiritual Awakening and Empowerment’ Asia Shepsut states that “Though some priestess traditions had been kept alive from the time of the Sumerian civilization of Uruk had reached as far along the Euphrates as Ebla in Syria, and Anatolia/Hittite contributions from what is modern-day Turkey to the north had some hold, the most striking influence was Egyptian.”

The Sumerian Inanna (Ishtar in Akkadian) migrated into the region by the first millennium BCE. Inanna was known to many regions by many different names. Astarte may have been the Canaanite Inanna. She was Asherah or Ashtoreth in the Torah and in western Semitic languages and Phoenician. She was Attart, Ashaa or Ishtar by the Hurrians. She was Athar-Venus in Arabia. She was Athirat in Ugaritic cultures.

In all forms, she was worshipped alongside the Canaanite Asherah. Asherah and Ashtoreth were both goddesses of love, whose symbol was a double-headed serpent. In many cases Astarte, and other goddesses who once had independent cults and mythologies became fused to such an extent as to be indistinguishable. Atargatis and Ashtarte became identified with the Greek Aphrodite.

Anat, Ellaat and Astarte were Levantine goddesses of Life. Anat, Ellaat and Astarte were confused, sharing attributes in common. Asia Shepsut explains that “In Canaanite art Anat/Ellaat/Astarte is always shown as unashamedly naked and sexually inviting, often holding the snakes of Gaia in her hands to suggest the communicative convulsions of life itself, as well as its eternal renewal due to the snake’s ability to shed its own skin for better replacement.”

While Ashtart (Astarte) and Anat were closely associated with each other in Ugarit, Egyptian and other sources, there is no evidence for conflation of Athirat and Ashtart, or Ashtart and Anat in Ugaritic texts.

In ‘The Return of the Divine Sophia: Healing the Earth through the Lost Wisdom Teachings of Jesus, Isis and Mary Magdalene’ Tricia McCannon believes that Ashtoreth was the Hebrew name for Asherah, rather than a separate goddess. She also suggests Asherah was identical to the goddesses Astarte, Ashtart and the Canaanite goddess Qeresh.

All these goddesses were associated with lions, horses or ibexes revealing her as Lady of the Lions and Mother of the Animals. Her association with lions links Asherah with Inanna/Ishtar, Kybele and even with the ancient Indian goddess Durga who first began in the Indus or Harrappan civilization. These goddesses all relate to the sun, and the lion’s courage and heart.

Anath

Anath (Answer, Testifies, To Rape or Responds Violently) was an Asiatic and especially West Semitic War-goddess, also given as An, Anatu, Atta.

Originally Anath was the goddess of the hunt and of fertility but became a goddess of war. Her titles were Lady of Heaven, Mistress of the Gods and Lady of the Mountain, associating her with the Sumerian Ninhursag. This gold pendant is possibly Anath or Astarte from Ugarit, dated 1500-1200 BCE. She as Hathor style hair and seems to be holding snakes aloft in each hand. Like Inanna and Ishtar, Astarte and Anath were called the Queen of Heaven.

In a myth from Ugarit of the battle between Baal and Yam, god of the Stormy Sea, Baal’s sister Anat uses henna, coriander and purple murex dye and goes on a bloody rampage against the worshipers of Baal until “heads were like balls beneath her” and she “plunged her knees in the blood of the guards, her skirts in the gore of the warriors, until she was sated with fighting in the house”. Later in the story Anat coloured El’s beard red with her gore, rejuvenating him.

Anath may have been a goddess of the dead, a role confirmed by her descent into the underworld to rescue her brother Ba’al. Like Persephone of Greece, she is the daughter who descends into the underworld voluntarily like Inanna and Ishtar, only she goes to rescue her brother-consort the god Ba’al from their brother Mot.

This gold plaque (20.4 cm high by 11.2 cm wide) depicts a naked goddess on a horse, probably Astarte or Anat, from Lachish dated to the late Canaanite period, thirteenth century BCE housed in the Israel Antiquities Authority.

Anath was celebrated throughout Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus or Harappan Valley, and much of the Levant. In Elephantine Island (modern Aswan) in Egypt, a fifth century BCE papyri mentions a goddess called Anat-Yahu (Anat-Yahweh) worshipped in the temple to the Hebrew God originally built by Jewish refugees from the Babylonian conquest of Judah.

Anath was celebrated throughout Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus or Harappan Valley, and much of the Levant.

Ellaat

Ellaat (also spelled Elat, al-Lat, Allat, Allatu, Alilat, Lat and Latan), literally means goddess. She is most probably an ancient Arabin goddess worshipped under various associations throughout the entire Arabian Peninsula. She was worshipped in both Palmyra, in modern day Syria and in Hatra, northern Iraq.

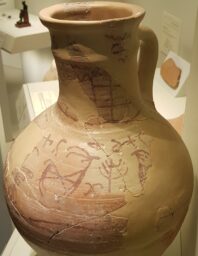

This Lachish ewer has a dedicatory inscription with the word Elat positioned immediately over the tree, indicating the tree as a representation of the goddess Elat.

Ellaat was used as a title for the goddess Asherah and Athirat, and she was recognised in Carthage as Allatu. A western Semitic goddess similar to the Mesopotamian goddess Ereshkigal was known as Allatum. Her iconography began to show the influence of Greek and Roman culture, adopting attributes of Athena/Minerva, a goddess of war.

Ellaat was mentioned as Alilat by the Greek historian Herodotus in his fifth-century BCE work histories who considered her the equivalent of Aprophite. According to the Greek historian Herodotus (c.484-425 BCE), the ancient Arabians believed in only two gods: “They believe in no other gods except Dionysus and the Heavenly Aphrodite; and they say that they wear their hair as Dionysus does his, cutting it round the head and shaving the temples. They call Dionysus, Orotalt and Aphrodite, Alilat.”

An Ugarit tablet describes the Canaanite El and his consort Ellaat, literally meaning the Universal Him and Her, who were the mother and father of the Hebrew God.

Astarte

Astarte is one of the oldest goddesses in the Middle East, mentioned in Sumerian cylinder seals as early as 2000 BCE. It is unclear whether Astarte was another name or aspect of Asherah, the same or different goddess to Anath. Astarte and Anath may have had complementary roles like the Egyptian goddesses, sisters Isis and Nephthys. An Egyptian twelfth century BCE papyrus they are called the daughters of Neith, the mother of the gods. The worship of Astarte was widely spread across the ancient Near East, and she was revered by the Syrians, Phoenicians, Canaanites and Egyptians.

This baked clay votive plaque of Astarte is believed to be Phoenician or Cypro-Archaic from the sixth century BCE. It was found in grave 11 at Tharros, Sardinia, and is not in the British Museum. She is in the classic pose, proudly holding her breasts and staring straight at the viewer, representing the concept that the divine feminine was the nurturer of the world.

The “woman at the window” on an ivory plaque from Arslan Tash is a motif used to represent a lady gazing at the world from her temple. The Lady In The Window motif generally represents a sacred harlot in service to a Goddess of Love, or the Goddess herself. This ‘lady at the window’ motif isn’t as confronting and arresting tiday as it was two thousand years ago. The gods and goddesses were portrayed in profile, side-on to the viewer, looking towards each other.

This motif was a revelation, a new direct gaze straight at the viewer, piercing into their very soul.

Astarte is the Hellenized form of the ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or the Northwest Semitic Athtart of the Canaanites and Phoenicians. Whereas Anath contains both the light and the dark, chthonic aspects of the Bronze Age goddess, Astarte contains only the light.

Astarte is closely related to the East Semitic Ishtar, worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. Like Inanna and Ishtar, Astarte was also associated with the morning and evening star.

An ‘Ugaritic Song of Athart’ (Astarte’s Hebrew name) reveals how worshippers viewed her, which is quite different from what modern scholars seem mostly to notice:

Athart the Huntress

Goes into the wilderness

She gazes here, she gazes there

She sees motion in a thicket

She tosses her spear a vast distance

She runs to the left

She lifts her eyes

She sees a doe resting

And the bull her spear has taken.

Asherah

Asherah, meaning Holy Queen, was the Queen of Heaven, Wisdom or Mistress of The Gods. Asherah was worshipped as the Holy Spirit and Divine Wisdom. A Canaanite earth and mother goddess, the Canaanites associated Asherah with the rivers and the sea, calling her Rabbatu athiratu yammi or Qaniyatu yammi, meaning Lady Who Traverses The Sea or She Who Walks On The Sea. This associates Asherah with the life-giving waters of the primordial ocean.

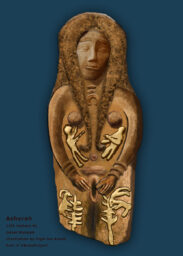

This exceptional figurine of a Canaanite fertility goddess depicts the goddess from both the interior and exterior perspectives, as she prepares herself for the delivery of twins. This figurine is presumably Asherah nursing the twins Shahar and Shalim, dated to the thirteenth century BCE and housed in the Israel Museum. Her symbols, the sacred tree and the ibex, appear on her thighs.

The twins, seen within her womb, clutch at her breasts. The figurine may represent Asherah, called the “sacred prostitute” or the “one of the womb.” According to myth, Asherah gave birth to the twin gods Shahar and Shalem. Symbols of Asherah, the sacred tree and ibex, appear on the goddess’ thigh. The figurine may have been held by women in childbirth.

Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. in ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’ believe the goddess Asherah was a Sumerian version of Inanna, who appeared in the Levant by the first millennium BCE. Asherah was often assimilated into the local goddess, making it tricky for scholars to tell them apart.

By the fourth century BCE, Astarte had superseded Asherah as the preeminent goddess of Sidon. The people of Sidon, who lived close to the sea, may have given her the titles Virgin of the Sea and Guardian of Ships, just as Mother Mary was called centuries later.

There is confusion whether Asherah, Astarte and Ashtart are different or the same goddess. In ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’ Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. describe the goddess Asherah as a Sumerian version of Inanna, who appeared in the Levant by the first millennium BCE. Asherah was often assimilated into local goddesses, making it tricky for scholars to tell them apart.

Asherah worship spread far and wide where she was given different, though similar, names in Canaan, Sumer, Syria, Babylon, and Arabia. Along with Astarte and Ashtart, she might also be the goddess known as Ellaat, (also spelled Elat, al-Lat, Allat, Allatu, Alilat, Lat and Latan), simply meaning goddess. All these goddesses were associated with lions, horses or ibexes revealing her as Lady of the Lions and Mother of the Animals.

This is a detail from a Mycenaean ivory unguent box from Mīna al-Bayḍā near Ras Shamra, Ugarit, Syria, from around 1300 BCE, now in the Louvre, Paris. Asherah takes the place of the Tree of Life who lets the ibexes or goats who eat from her hands. As the Tree of Life, Asherah was worshipped as the Giver of Life. A lion, fallow deer and ibexes seem to be associated with Asherah. Pubic triangles seem to be identified with Athirat/Asherah who wears a Hathor wig and has a central symbol of a branch or stylised tree.

Asherah was worshipped in Ugarit, Tyre and Sidon with numerous tablets discovered, along with terra-cotta goddess figurines and a statue of a nude woman standing between two lions. Her association with lions links Asherah with Inanna/Ishtar, Kybele (see my blog: The Goddesses of Anatolia) and even with the ancient Indian goddess Durga who first began in the Indus or Harrappan civilization. These goddesses all relate to the sun, and the lion’s courage and heart.

This old pendant could be Astarte or Asherah. Found at Minet el Beida, Ugarit it was made around 1500-1200 BCE and is now in the Louvre. This pendant shows Egyptian influence with the goddess reduced to a head with Hathor style hair, breasts and a vulva. This was the goddess as the Great Mother, Giver of Life. Asherah was associated with Wisdom and was Mistress and Creator of the Gods. Most often she was in her crone phase, an old wise woman and matriarch. Asherah used her powers of persuasion on her husband El in order to mediate between him and other gods, and she acted as co-ruler of the gods. Asherah also had a youthful aspect, ruling over sexuality and motherhood.

From at least the thirteenth century BCE, Asherah became the principal goddess of the Canaanite pantheon. Ugarit cuneiform tablets speak of Asherah, her daughter Anath or Ishtar, and honour Asherah as the most important goddess. Inscriptions to the goddess in Canaan describe Asherah as Celestial Ruler, Mistress of Kingship, Mother of all Deities.

Clay tablets found at Ugarit depict the Canaanite god El with his divine consort Asherah, the supreme female deity of all Canaanite deities. The Ugarit texts reveal Asherah was particularly popular across the ancient Near East from Egypt worshipped during the New Kingdom (1550-1070 BCE) to Mesopotamia. Asherah was worshipped alongside the male god as his consort and wife from 3500-500 BCE.

Asherah was The Holy One. Asherah was present and participated in the creation of all things, Genesis, and was known as the Creatress of The Gods. Her other titles were Mother of the Gods, Lady of the Sea and the Lion Lady.

In Egyptian depictions Asherah was naked standing astride a lion, much like Inanna/Ishtar had been represented for thousands of years. Some believe Asherah is shown riding a lion, holding lotus flowers and serpents in raised hands, and was known in Egypt as Qadashu or Qetesh.

During the period of Egyptian rule in Palestine the Hathor cult penetrated the region so extensively that Hathor became identified with Asherah. In Egypt and Canaan, she was associated with Hathor although Asherah tended to have a fierce, motherly aspect to the bovine Hathor. The interchange between the tree and the pubic triangle prove that the tree symbolises the fertility goddess Asherah.

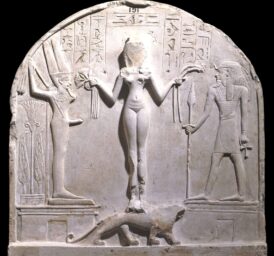

A Canaanite relief shows Kadesh/Qedeshet as a slender, sensual, long-haired maiden astride a lion, flanked by the godlings Min and Reshet, Min’s penis erect. This last image that intrigues me comes from Egypt. This looks surprisingly similar to the Metternich Stela, a magico-medical Horus on the Crocodiles stele that dates to the Thirtieth Dynasty of Egypt around 380–342 BCE.

Now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, this stele (or cippus) is loaded with information and the main figure in the upper register looks remarkably similar to the stele of a goddess from Deir el-Medina, Egypt from the Nineteenth Dynasty (1292-1198 BCE).

This is the upper register of a limestone stele of chief craftsman Qeh depicts a naked goddess identified as “Ke(d)eshet, Lady of Heaven” flanked by the Egyptian god Min and Syro-Palestinian god Reshep, now in the British Museum (EA 191). Her name Qdš(-t) simply means holy and so it can represent almost any goddess, including Anath, Astarte, Asherah and Athirat. In Egypt, Qedeshet was honoured with such typical titles as Lady of Heaven and Mistress of All the Gods, which could apply to any goddess in Egypt.

Qudšu

Another possibility is a Canaanite goddess Qudšu (also written in English as Qedesha, Qudshu) who was also worshipped in Egypt as Qetesh (also Qodesh, Qadesh, Qedesh, Qetesh, Kadesh, Kedesh, Kadeš or Qades) and was usually depicted nude, with curly hair, standing on a lion with raised arms carrying lotus flowers in one hand and serpents in the other. The word qdš also appears in the Pyrgi Tablets, a Phoenician text found in Italy that dates back to 500 BCE.

The gold plaque image found at Tel Lachish is from the late Bronze Age (thirteenth Century BCE) is a Canaanite relief of Qedeshet standing atop a horse, which was her more common animal outside of Egypt. The horse has a giant plume attached to its forehead and is wearing armour. Qedeshet is nude except for her elaborate hair, hair band, and feathered hat with moon horns. She carries lotus blossoms in each hand.

Qedeshet, Sacred One, is a Syrian goddess of love and war, the same as Virgin Anath, also given as Kadesh (Holy Woman or Sanctuary). To the Egyptians, she was Hathor, the Eye of Ra, and Mother of All Gods.

Kadesh was also used to praise the holiness of many a significant goddess, and recurs especially in Ugaritic literature as one of the most common epithets for Asherah. Qedeshet was sexually aggressive, to the highest degree, and was incorporated into the Hebrew concept of Asherah, whose priestesses were called Kedeshot and whose priests were called Kedeshim.

Qudšu, with a Semitic root meaning sacred or holy, could be an appellation for the goddess Asherah, or a divine epithet for both Asherah and the Ugaritic goddess, Athirat, or a deity in her own right. From a basic verbal meaning to consecrate, to purify, Qudšu could be used as an adjective meaning holy or as a substantive referring to a sanctuary, sacred object, sacred personnel. The root is reflected as q-d-š in Northwest Semitic and as q-d-s in Central and South Semitic. In Akkadian texts, the verb conjugated from this root meant to clean, purify.

According to the texts found in Ugarit, Asherah was known by various names such as Asherah, Qudshu, Elath. Qudsh or Qudshu meant holy or sanctuary. This idea of a holy haven is reminiscent of a mother goddess who cares and nurtures for her children, keeping them safe from harm.This Qetesh painted limestone relief plaque is called Triple Goddess Stone. The title reads “Qeteshet, Astarte, Anat” and is dated to the time of Rameses III (1198-1166 BCE).

Tricia McCannon in ‘The Return of the Divine Sophia: Healing the Earth through the Lost Wisdom Teachings of Jesus, Isis and Mary Magdalene’ suggests that Ashtoreth was the Hebrew name for Asherah, rather than a separate goddess. She also suggests Asherah was identical to the goddesses Astarte, Ashtart and the Canaanite goddess Qeresh. However, modern Egyptologists, such as Christiane Zivie-Coche, do not consider Qetesh to be the same goddess as Asherah, Ashtart (Astarte) and Anat, but a goddess developed in Egypt possibly without a clear forerunner among Canaanite or Syrian goddesses, though given a Semitic name and associated mostly with foreign deities.

Qetesh was a goddess who was incorporated into the ancient Egyptian religion in the late Bronze Age. Considering there are clear references to Qetesh as a distinct deity in Ugaritic and other Syro-Palestinian sources, she is considered an Egyptian deity influenced by religion and iconography of Canaan, rather than merely a Canaanite deity adopted by the Egyptians. In Egypt, her epithets were Lady of Heaven, Mistress of All the Gods, Lady of the Stars of Heaven, Beloved of Ptah, Great of Magic, Mistress of The Stars, and Eye of Ra, Without Her Equal. A connection with Ptah or Ra evident in her epithets is also known from Egyptian texts about Anat and Astarte.

I hope this helps to get a feel for the thousands of goddesses who are available for us to work with. This is the long lost her-story of goddess worship that was once integral to a feminine spiritual path.

Which place and period in her-story resonates for you?

Which goddess draws your curiosity?

Examples of Canaanite goddesses: Anath, Ellaat, Astarte, Asherah