The Goddesses of India

I first went to India in my twenties. I stayed for six months, four of that studying hatha yoga on the shores of the Ganges in Varanassi with Sunil with the infectious laugh. Since my twenties I have been pulled back to India half a dozen times, and each time has been life changing.

Aaah India! What a crazy mixed-up land! I love India with all my heart, but boy does it get you processing all your stuff! Any unresolved issues tend to come rushing to the surface to be looked at and in my twenties I had tons of it!

I travelled around a bit going to a Monlam Chenmo, Great Prayer Festival, an annual Tibetan Buddhist gathering that takes place where the Buddha first became enlightened, in Bodh Gaya in Bihar, India. I spent a magical time in Rajasthan at Jaipur, Jaisalmir, Pushkar and Udaipur. I went hiking in the Kulu Valley, in Himachal Predesh and went to a full moon rave in Manali. I stayed with a nomadic shepherd family in Dharamshala where I personally met the Dalai Lama and received his blessing.

But the place that keeps drawing me back to in this vast land is Rishikesh in the foothills of the Himalayas on a north-western region of India called Uttarakhand. Not much further into the mountains is the source of the Ganges River.

But the place that keeps drawing me back to in this vast land is Rishikesh in the foothills of the Himalayas on a north-western region of India called Uttarakhand. Not much further into the mountains is the source of the Ganges River.

In 2018 I was lucky to be taken to a forgotten cave underneath Laxman Jhula where Shiva has been worshipped for hundreds of years., although its more likely thousands of years old. This cave might be the original reason Rishikesh became a pilgrimage site. All the wise men and saints who walked this way have visited this cave.

There are three altars to Shiva inside and one outside the cave. Somewhere along the line someone created an outer room to enter the cave from, with concrete walls and floor meeting the natural rock face, probably to protect the cave from monsoonal floods from the Ganga. The cave has been protected, hiding its importance from the outside. A metal gate bars intruders. Most people do ont even know it is there. Due to the sacredness of the cave I did not take any photos inside.

To the side of the concrete room is another smaller crevice in the rock (too small to be called a cave) with a statue built into the rock face. Next to this one, on a ledge for an altar, sits a Durga statue….so who is the other goddess? This is Bagala Mukti or Pitambari Devi in Rishikesh. She is one of the 10 forms of Kali.

This image nineteenth century watercolour painting on paper is of Bagalamukhi Matrika. Bagala Mukti is associated with the throat chakra, soft palate, voice and speaking. She holds a club in one hand and a demon’s tongue in the other – thumping it with her club. Bagala Mukti can stop thought loops and paralyse unhelpful thoughts. Bagala Mukti protects against unwanted thoughts and energy. This is her superpower.

Although the Shiva altars were being tended, no one has been tending the Bagala Mukti and Durga altar. I was one of a handful lucky enough to enter this sacred cave to tend the altar with my teacher Chameli Ardagh.

We lovingly swept the whole area, cleaned every surface, and spent toime cleaning the altar of Bagala Mukti and Durga. The statue of Bagala Mukti is nothing really – a few curves in concrete on a wall painted black with eyes and earrings. But you can feel she’s old and treasured and was once magical in her ability to transmute the woes of her devotees.

After the area was cleaned we decorated the altars and the floor with marigold flowers.

This sacred place is so secret and forgotten there were no holy men guarding it, so Chameli was free to hold a ceremony her way. When the whole space looked beautiful Chameli held a ceremony to initiate us into the mantras of Bagala Mukti, then we stepped individually first into the Shiva cave.

The Shiva cave had an incredibly powerful vibration. Wave upon wave of energy hit me, coming off the altar with a bang. It was difficult to stay for very long, it was that powerful. Obviously, this cave was well used for a long time.

We then entered into the little cave of Bagala Mukti one at a time. There was only enough room for one person to crouch or sit in front of the altar. For me, this felt like meeting a very old friend. I cried with joy.

I touched my forehead to the floor in front of her and could feel the foreheads of millions of women before me. I felt myself take my seat amongst the millennia of yoginis before me. I stepped onto this path very consciously.

A Living Goddess Tradition

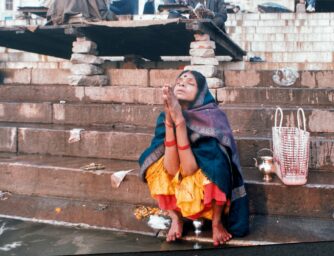

This is what is so incredible about India. There is a living goddess tradition that continues unbroken to this day. India stands alone amongst all of the ancient goddess-worshipping countries who have continued to venerate the goddess.

It is impossible to do justice to the sights, smells and emotions of India and experiencing the devotion of worshippers firsthand. Millions continue to worship the goddess with her ongoing presence.

Most of us have never been exposed to a living goddess tradition. In Western culture we were with the belief that there is one god who is male and is the supreme creator of all. As women, we have lost an understanding of a feminine face of god, a divine feminine. Not only that, whether conscious or unconscious, the idea of worshipping a goddess brings up fear.

This fear is not irrational. We have been persecuted for this in the past and our collective consciousness remembers and is fearful. But that is not the case anymore. Women in Western society have a phenomenal opportunity to reclaim our feminine wisdom and remember what it is to be an empowered, passionate woman living with purpose!

Being a living tradition, Hindu goddesses continue to change and evolve, even though much of what we know about her was written long ago in the Vedas, the ancient sacred text. Through sacred texts and practises we can learn about the many great goddesses and how to connect with them. Nothing compares to firsthand experience. India gives us a firsthand visceral experience of goddess worship of incredibly powerful goddesses.

To understand the goddesses of today we need to go as far back as we can, back to the Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation (7000-600 BCE BCE)…

The Vedas

Archaeological artefacts found so far in the Indus-Sarasvati Civilisation, also known as the Indus Valley Civilisation or Harappan Civilisation, dates back to the seventh millennium BCE, making it one of the oldest in the world.

The Indus Valley civilization was thriving by 2500 BCE, with large cities Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa whose citizens may have enjoyed a higher standard of living than those in Sumeria and Egypt.

This civilisation thrived between about 3300-1300 BCE and was centred around agriculture and trade. From archaeological evidence we know these people of the Indus-Sarasvati civilisation believed in multiple gods and goddesses and worshiped them through various rituals and offerings.

Incredibly, trade during the Bronze Age (c.3500-1250 BCE) created an exchange of beliefs from Old Europe and the Near East all the way to the Indus Valley. The people of the Indus Valley traded with Sumeria as early as the fourth and third millennia BCE, with identical seals discovered in the Indus Valley, Eshnunna in Mesopotamia and ancient Elam (modern day Iran) dating from 2300 BCE.

Sumer and western India were in close contact in at least the third millennium BCE with the trading routes by land and sea allowing a transference of ideas along with products. Indian and Mesopotamian religion was already ancient wisdom by the time their beliefs spread into the rest of Asia and the European continent.

Joseph Campbell in ‘The Hero with a Thousand Faces’ compared the mythic imagery of Western Europe to Asia and concluded that the same imagery was used in the Aegean and in India. He found the goddess as a cow and lioness, the Tree of Life, while the god was the consort to the goddess, symbolised by the bull, with his fate connected to the waxing and waning phases of the moon.

The theory is that the myth originated in the Near East and was assimilated into these other cultures along the trade routes on land and sea. ‘The Mythic Image’ by Joseph Campbell believes in the fourth millennium BCE “it is not that the divine is everywhere: it is that the divine is everything”.

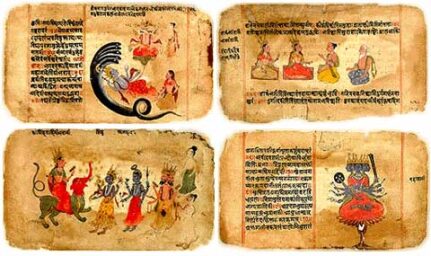

The Vedas, Hindu sacred scriptures, are ancient, channelled wisdom that continue to be explored in an unbroken, continuous tradition. The Vedas existed in oral form and were passed down from master to student for generations. The Vedas were carefully memorised to keep what was originally heard intact.

Eventually the Vedas were written down in Sanskrit around 1500–1200 BCE, although they might be much older. Sanskrit is an ancient, multi-layered language loaded with meaning, and reciting it is thought to be powerful even if we do not understand what we are saying.

The Vedas were composed by ancient rishis (sages) through visions and revelations gained during meditation. The rishis contemplated the energies of deities, seeing them as light bodies and as patterns or geometric forms called yantras. Yantras and shamanic art can impact the viewer directly through an energetic transmission that bypasses language.

Using their own mystical experiences, the rishis created practices for a devotee to access these energies emotionally, mentally, and even physically. The rishis created a system for others to follow.

Vedic descriptions of Aditi are vividly reflected in the countless Lajja Gauri idols – depicting a faceless, lotus-headed goddess in birthing posture – that have been worshiped throughout India for millennia.

The Rig-Veda is India’s oldest epic poem and contains glimpses of the culture that existed before Aryans migrated to the region. In the Vedas the Great Goddess of the Indus Valley looms large, taking the mysterious form of Aditi, the Vedic Mother of the Gods.

Aditi is mentioned about 80 times in the Rig-Veda, and her appellation (meaning without limits in Sanskrit) marks what is perhaps the earliest name used to personify the infinite.

In the Rig-Veda hymn Devi Sukta, Devi declares her all-encompassing supremacy:

“I am the Sovereign Queen; the treasury of all treasures; the chief of all objects of worship; whose all-pervading Self manifests all gods and goddesses; whose birthplace is in the midst of the causal waters; who in breathing forth gives birth to all created worlds, and yet extends beyond them, so vast am I in greatness.”

In the Rig-Veda, women appear to have been powerful were free to own property, participate in feasts and rituals and, unlike modern Indian culture, widows could remarry.

In a later text, Drapaudi married five brothers at the same time, suggesting polyandry was common and women enjoyed many cultural liberties in the transitional Indian Epic Age (2000-1000 BCE).

Polyandry continues in the foothills of the Himalayas and in Tibet. When I walked the Langtang Track in 1995 I met a local Nepali guide who described his culture that included a woman marrying several brothers at the same time, explaining that this was to keep the birth rate low enough for the land to sustain them.

In the Rig Veda cows, mothers, goddesses and rivers are synonymous with each other, and they are restrained alongside their innate fertility by both serpent and mountain; easily interpreted from Hindu, Buddhist, and global cosmology as an axis mundi or tree symbol.

The tree draws up the waters from the earth just as the mountains of the Himalayas, known in the Veda as parvata, are the source of rivers in India and can be conceived of as performing a similar function.

The Upanishads, Vedic texts that contain some of the earliest religious concepts of Hinduism and Buddhism, were composed around 800–300 BCE.

A growing number of scholars are cautiously suggesting the Rig Veda dates to the third or even fourth millennium BCE, and the other three Vedas are most likely just as ancient.

However, recent geological discoveries have thrown these dates into dispute. The book Rivers of Rig Veda describes the flow of the rivers, describing the Sutlej as a tributary of Sindhu and Yamuna as a tributary of Ganga in Rig Veda. The Rig Veda records the period after the separation of Sutlej and Yamuna from Sarasvati, with a mid-course of Sarasvati drying up by 1900 BCE.

The Goddess

The prominent religious icons were mother goddesses or Earth goddesses who represented the divine feminine and was closely linked with fertility and were important aspect of Harappan culture. These goddesses were often represented by stones and natural energy was seen as a feminine principle.

The prominent religious icons were mother goddesses or Earth goddesses who represented the divine feminine and was closely linked with fertility and were important aspect of Harappan culture. These goddesses were often represented by stones and natural energy was seen as a feminine principle.

These great goddesses began during the Bronze Age (5000-1400 BCE) except in the Indus Valley where the goddess was present from the Neolithic Age (10,000-3,000 BCE) …

The vast majority of statues found are thought to be a Mother Goddess. So far archaeological finds suggest all across India was once egalitarian Goddess-worshipping cultures. In the south of India, the Dravidians lived in the Deccan Plain. The Dravidians inherited property through the female line. Pre-historic Dravidian sites depict the bull horns of sacrificial sites found in Çatalhöyük and Knossos.

But recent finds are challenging the age and perceptions of the goddess in India…

Bone Image from Uttar Pradesh (23,000-20,000 BCE)

Unfortunately I’ve been unable to find an image of a bone figurine of the Great Mother discovered in the Belan valley, Mirzapur district of Uttar Pradesh. This area was still revered at Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro in the Indus Valley in 2500 BCE. She has broad hips and large sagging breasts, similar to female figurines from Western Asia and Eastern and Western Europe that are considered to be Mother Goddesses or Fertility figures.

What is more remarkable is that archaeologists can identify who she is based on the religious beliefs that continue as a living stream of goddess worship.

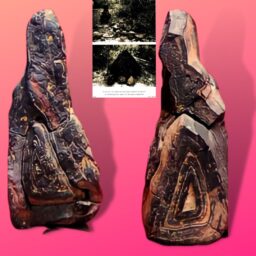

Baghor Kali (11,000-9000 BCE)

In 1982 archaeologists discovered that the entire region of a site named Baghor-1 in Sihawal tehsil, at the feet of the Kaimur range in Sidhi district of Madhya Pradesh, had shrines scattered throughout the countryside and villages, including one to Kalika Mai with a near-perfect triangular form and pattern, at the house of the Baghor-1 site watchman.

In Medhauli village at the base of a big neem tree there is evidence that the original Shakti-worship of the ancient Palaeolithic hunter-gatherers had not stopped but continued and thrived among their tribal descendants and later peoples.

The Baghor Kali is a 15cm triangular sandstone, selected for its natural pattern of five concentric triangles ranging in colour from red-brown to yellow-brown. Even though this 10,000-year old goddess is exhibited upside down inside a dusty glass cabinet, she exudes power.

The people of this region are the Kol and Baiga tribals, ancient inhabitants of these parts with Dravidian affiliation. It is only because of the connection between the living traditions of these people that archaeologists realised the significance of the Baghor Kali.

These people continue use this same type of colourful natural stones with concentric geometric laminations, often in the form of triangles, as a symbol for the female principle. They call the Mother Goddess Mai, variously named Kerai, Kari, Kali, Kalika or Karika.

Mai is firmly believed in not just by the Kol and Baiga but also caste Hindus and even Muslims, who have coconuts offered to her by the hands of the former. The goddess protects all and bestows health and prosperity to all. At all these places offerings of sindoor (vermilion) and coconut are made, and heads are shaved to honour Mai.

The inverted triangle is perhaps the oldest symbol of the divine feminine, representing the yoni – the womb of creation. This exalted symbol finds its full, sophisticated expression in the ‘yantra’ forms of tantric tradition.

Considered to be the abstract, geometric forms of Hindu deities, the highest and most common of yantras is held to be the Sri-Yantra or Sri-Chakra. Composed of five inverted Shakti triangles intersecting intricately with four upright Shiva triangles, this pattern represents the entirety of creation as being born from the union of Shiva and Shakti in the form of goddess Lalita.

All other yantras are said to be derived from this yantra, and this belief seems to be upheld rather strikingly if the four upward-pointing Shiva triangles are removed from its design. The form of five inverted concentric triangles is the pattern on the Baghor Kali stone, the symbol of pure Shakti, the yantra of the primordial Kali Mai.

Devi

She is eternal, the Mother Goddess, Mother Nature, the mother of the gods. Entire ages, eras, civilisations, cultures, religions, even gods come and go, but Mai is forever.

In the Vedic period Devi came to represent the female energy or Shakti (power) of her husband Shiva. As Shakti, she became the powerful spiritual energy necessary for the god to act.

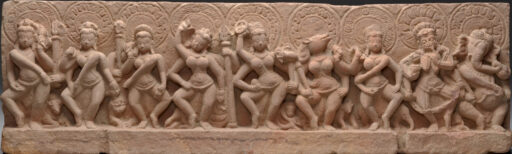

Here, sculpted in red sandstone, are the Seven Mother Goddesses (Matrikas), flanked by Shiva (left) and Ganesha (right) dated the ninth century in Madhya Pradesh, India.

All Hindu goddesses are viewed as different manifestations of one Great Mother known simply as Devi, literally meaning goddess.

Every Hindu has their own major deities and every god and goddess has hundreds of names and attributes each. The great Hindi trinity of Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva all have cosmic consorts Saraswati, Lakshmi and Parvati.

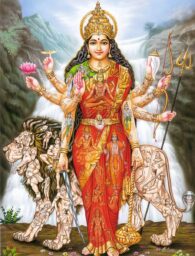

Behind them is Mahadevi or Maheshwari, the all-embracing Neolithic Mother Goddess of India. This image is a modern interpretation of Mahadevi as the Supreme Goddess encompassing all divinities. Dev was the Sanskrit word for god, meaning shining or bright, just as Devi was Sanskrit for goddess. Devi the Great Goddess revitalises all the other deities and gives them power to perform their cosmic functions.

She is Shakti— Mother Goddess of Sanatana Hinduism. The goddess appears in multiple forms. As an independent goddess she is often given the generic name Devi meaning simply goddess.

Devi is multi-faceted, known by myriad names and personified in many forms. Devi is one and she is many. She is Devi, the Great Shining One in her infinite manifestations and as collectives of numerous goddesses.

Devi is first seen as a cosmic force, where she destroys demonic forces that threaten world equilibrium, and creates, annihilates, and recreates the universe. In her gentle, radiant dayini (meaning She Who Bestows) form, she is the gracious donor of boons, wealth, fortune, and success. As heroine and beloved, Devi came down to earth and provided inspiration for earthly women.

The world of goddesses encompasses both the inner and outer universe, and each goddess is an aspect of Devi. Goddess is understood as a field of consciousness of Devi as the one and the many. She appears in many forms. Some she conceals, others she reveals, and yet all her infinite forms are ultimately different aspects, moods or fields of her cosmic and earthly magnificence.

Devi had many names and aspects. She is Vindhyavasini, Kanya (the Virgin) and Mahamaya (the Illusion). She is Bhutanayaki, (the Queen of the Bhuta), who were ghosts and goblins that were said to haunt graveyards, make the dead live again and trick the living in order to feast on their flesh.

Devi has a benevolent side as Ma, the gentle approachable mother. As Uma, she is represented as both beauty and light. As Jaganmata, or Mother of the World, Gauri (Yellow and Brilliant or Golden), Bhavani, Haimavati, and Parvati (the Mountaineer), she assumes cosmic proportions, destroying evil and addressing herself to the creation and dissolution of the worlds. This Chromolithograph depicts Parvati riding a lion to present her son Ganesha to her mother Menaka.

Closely associated with the land, villagers in rural India paid tribute to Devi as the Earth Goddess, adorning branches of trees and placing shrines within them which carried her image. Smooth, oval-shaped stones also marked her sacred sites.

Women are her channels and perform rituals, including rites for the dead and ceremonies to promote fertility and fruitfulness of the land. Devi appears as a semi-divine force, manifesting herself through fertility spirits, and other supernatural forms. Devi is represented by women saints born on earth but endowed with spiritual and other-worldly powers.

The words Devi and Shakti are also used more generically to reference any female Hindu goddess, especially Parvati, Lakshmi (pictured) and Saraswati. Each Hindu goddess had her owen identifying features and attributes. Devi also manifests under the titles of Gauri, Uma, Sati, Aditi, Maya, Ganga, Prakriti, Gayatri, Tara, Minaksi, Mahadevi, Kundalini, Durga, Kali, Chamunda and in many other guises.

The Goddess became united in a Divine Marriage with the gods of the male trinity: Sarasvati with Brahma,, and Parvati, Kali and Durga with Siva. Once given a priestly blessing, veneration of the goddess as the god’s consort was incorporated in the regular rituals.

It is in her fiercer personification that Devi is most frequently worshipped as Durga. In this lithograph from 1931, Durga, the Terrible or the Inaccessible. Durga has ten arms, an impressive armoury of weapons, and she rides a magnificent lion or tiger.

This side is further manifested in her dark side can also take the form of the fearsome black Kali, Kalika or Syama (the Black Goddess); Candi or Candika (the Fierce), in which guise she killed many a demon or asura; and Bhairavi (the Terrible).

Worshippers seek her favours and dark powers by making blood sacrifices and performing rituals in the ceremonies of Durga-puja, Carak-puja, and the Tantrikas to call on Durga’s sexual and magical powers.

There are rituals and sadhanas (practices) for practitioners to harness the energies and qualities of particular goddesses. These practices assist in all rites of passage within a practitioner’s life, such as birth, menstruation, sex, illness and death as well as to gain worldly and spiritual powers.

I hope this helps to get a feel for the thousands of goddesses who are available for us to work with. This is the long lost her-story of goddess worship that was once integral to a feminine spiritual path.

Which place and period in her-story resonates for you?

Which goddess draws your curiosity?

Examples of Indian goddesses: Durga, Kali, Parvati, Lakshmi