What’s with the Skull, Mary Magdalene?

Western culture does not do well with death. We no longer have rituals and practises to support the grieving. We seem to find the whole idea of death uncomfortable, living in denial of our own essential mortality.

In ancient times all the way into the nineteenth century, death was a visible reality. With death rates so much higher, the dying were cared for at home and funerals were held in the home. Death was not hidden from sight in a hospital or funeral home.

In the Near East there were ways to understand death and to help those grieving through their darkest days. We are out of practice.

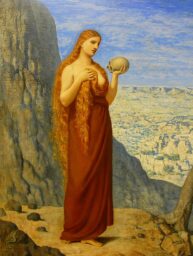

But what is with the skulls that are depicted so often in representations of Mary Magdalene?

In orthodox Christian iconography Mary Magdalene is identified through a skull, a jar of ointment and a book. (For more on the symbolism of the book see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Open Book’. For the ointment jar, see ‘Mary Magdalene and Grief’)

In orthodox Christian iconography Mary Magdalene is identified through a skull, a jar of ointment and a book. (For more on the symbolism of the book see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Open Book’. For the ointment jar, see ‘Mary Magdalene and Grief’)

According to the article ‘Mary Magdalene; Saint in Life and Legend’ by Suzannah Gerber that Mary Magdalene “fit into two classifications of visual iconography: that of the beautiful Magdalene, living devotee of Christ; and that of the sorrowful repentant ascetic.”

Mary Magdalene is represented as a “beautiful sinner” or as repentant and gradually becoming more “righteous”. Finally, she becomes saintly when her sorrow and grief matures into rapture after the resurrection.

In the Penitent portraits there were often a skull, book and crucifix associated with penitent portraits, not just of Mary Magdalene. Portraits of a penitent Mary Magdalene as a beautiful seductive sinner became the standard in Renaissance depictions of her. She was seen as a Redeemed Penitent St. Mary.

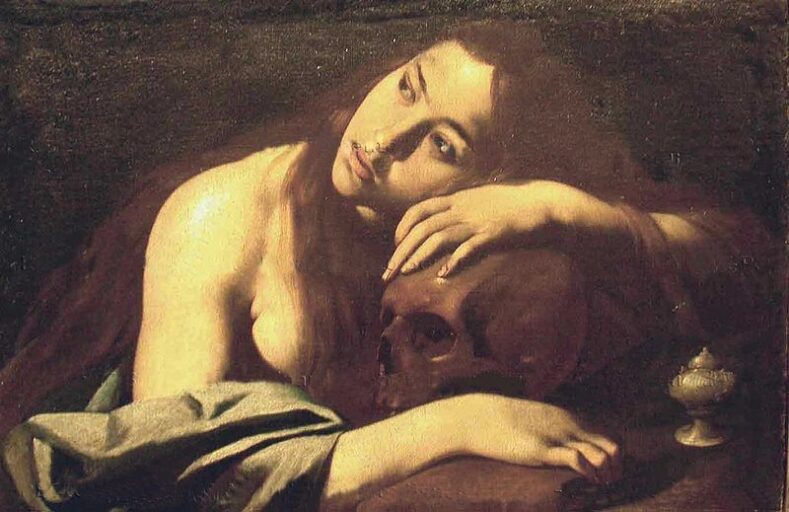

This painting is from the Flemish School in the thirteenth Century of Mary Madeleine en prière. (For more on the jar read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Anointrix’)

Another theory is that the skull represents Mary Magdalene’s connection to the site of Jesus’ crucifixion, Golgotha (the place of the skull).

Then there is the theory that the skull is of Sarah Damaris (also known as Sarah-Tamar), daughter of Mary Magdalene and Jesus. She is believed to have been born in Egypt after the crucifixion and brought to France when she was twelve. You’ll remember Sarah who came by boat to France. Perhaps this was Jesus and Mary Magdalene’s daughter, perhaps not.

In the Bible, as an adult in her early twenties, a woman named Damaris was present with Dionysus the Areopagite when apostle Paul caused a riot. Paul, also known as Saul, who had never met Jesus, but wanted to ‘be like Jesus’, tried preaching his own version of Christianity in Ephesus. Paul’s preaching upset the local matriarch goddess Artemis, prompting a riot as described in the Book of Acts, chapters 19 to 41.

The rest of the orthodox legend goes that Damaris was beheaded at around the age of twenty-two in Corinth, Greece, due to political ramifications from the riot at Ephesus and Paul’s teachings.

Discovery of Her Relics

This skull iconography began with a discovery. This discovery was startling and would have shaken the Christian world to its core.

A skeleton was discovered, including a skull, with a sign on the marble sarcophagus stating that these were the relics of Mary Magdalene.

When the sarcophagus was opened for the first time all present testified of a “wonderful and very sweet smell” that came out of the sarcophagus. These remains were later authenticated by Pope Boniface VIII. The jaw and lower leg bones were missing.

It was only after this discovery that Mary Magdalene was first depicted with a skull, beginning around 1279.

Even today the skull is venerated, and is taken annually in procession through the streets of Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume on 22 July, Mary Magdalene’s Feast Day. There is no definitive way to confirm that these relics belong to Mary Magdalene, although analysis suggests it belonged to a woman who lived in the first century.

The discovery and veneration of the relics, especially the skull, inspired artists to represent Mary Magdalene with a skull. The skull came to symbolise repentance, penance, and mortality, reflecting her association with a life of contemplation and solitude after encountering Jesus.

So does this skull represent herself, her penitence for her first husband or her daughter? Or is it meant to be purely allegorical and a nod to our mortality? Or can it represent all of the above for those with eyes to see and ears to hear?

This begs the question: if she was so famous in France how did they lose the relics of such a revered saint that they were rediscovered in 1279?

How the Relics Were Lost

Construction of the Basilica St Maximin did not begin until 1295. It was never fully completed 0- the grand facade never even begun.

Construction of the Basilica St Maximin did not begin until 1295. It was never fully completed 0- the grand facade never even begun.

Initially, between the first to the fifth centuries the remains of Mary Magdalene’s body lay in Saint-Sidoine.

This changed when the Saracens invaded Provence in 710. The relics were transferred in secret to avoid the desecration of St Marie-Magdalene’s relics. For the next five centuries, the location of the body of St. Mary Magdalene will remain unknown.

When the sarcophagus was discovered again in 1279, writing on papyrus dated 710 attested that the bones were of St. Mary Magdalene in the presence of the Archbishops of Aix and Arles, and many other prelates.

This papyrus with the relics stated: “The year of the birth of the Lord 710, the sixth day of December, at night and very secretly, under the reign of the very pious Eudes, king of the Franks, during the time of the ravages of the treacherous nation of the Saracens, the body of the dear and venerable St. Mary Magdalene was, for fear of the said treacherous nation, moved from her alabaster tomb to the marble tomb, after having removed the body of Sidonius, because it was more hidden.”

During the solemn Elevation of the body St Mary Magdalene in 1280 a tablet of wood smeared with wax was discovered with the words: “Hic requiescit corpus beatae Mariae Magdalenae”, translating to “Here rests the body of blessed Mary Magdalene”. The estimated age of the tablet is between the first and fourth centuries.

A testimonial letter destined for the pope was signed by the four Prince Archbishops and three bishops, describing these events and was kept for a long time in the reliquary of St Maximin along with the translations of 1281 and 1283.

In 1295, the lower jaw, housed at St John Lateran in Rome, was reunited with the skull from the sarcophagus of St Maximin. Pope Boniface VIII published a Pontifical Bulle for the establishment of Dominicans at St Maximin and at La Ste Baume.

Basilica St Maximin

It took years of research and self-discovery before Mary Magdalene gave me permission to go to sit in front of her relics. It was June 2018 when Mary Magdalene strolled into my consciousness.

It took years of research and self-discovery before Mary Magdalene gave me permission to go to sit in front of her relics. It was June 2018 when Mary Magdalene strolled into my consciousness.

I vowed to go to France, giving myself the arbitrary date of October 2019 – my birthday month. I did not know where I needed to go (or why) but I knew it was important to go there physically.

In 2023 I finally felt I was allowed to go to Provence, where her legend truly comes alive.

My mother and I travelled to France to walk in the footsteps of Mary Magdalene and hear the local legends of Provence.

Begun in 1295, the crypt of the Basilica St Maximin was not completed until 1316, when the church was consecrated. In 1348, the Black Death interrupted construction, killing half the local population. Construction did not resume until 1404, and the sixth bay of the nave was completed in 1412.

Work continued until 1532, when it was decided to leave the basilica without a finished west front or portal or bell towers, features that it lacks to this day. The plan has a main apse flanked by two subsidiary apses. Its great aisled nave is without transept. The nave is flanked by sixteen chapels in the side-aisles.

It is odd to come to such a profoundly important Christian site and find it so incomplete, the front facade never begun. Only these great wooden doors decorate the facade, depicting the twin reliefs of St Maximin and St Mary Magdalene.

We had been given a history lesson outside, but I had very little understanding of what lay within. Walking beneath their benevolent gaze was a moment I will never forget. I had no idea what I was going to find inside, but I entered with all of my spidey senses on high alert, ready to feel into the energies of the place.

The energy hit me almost immediately – was wave of strong love that was much stronger than any church I had ever entered.

The Power of Relics

It is easy to discount relics as superstitious nonsense. I certainly did. My understanding of relics was that they were used to access the saint. Pilgrims would walk for years to sit in front of the saint’s relics to pray, asking the saint for them to intercede on their behalf.

It is easy to discount relics as superstitious nonsense. I certainly did. My understanding of relics was that they were used to access the saint. Pilgrims would walk for years to sit in front of the saint’s relics to pray, asking the saint for them to intercede on their behalf.

The whole point of the Camino de Santiago, an 800 km walk through northern Spain, was for pilgrims to reach Santiago de Compostela, a city whose basilica housed the relics of Santiago – Saint James.

Christian pilgrims walked from all over Europe, usually for penance, knowing they would never return home, to pay their respects and ask favours of St James. The Camino de Santiago also became an initiation route used by holy orders such as the Knights Templar, who guarded the route with castles scattered along its path.

It took a relic in Spain, while walking the Camino de Santiago, for me to discover their power. I sat down in the pew, eyes closed, to feel into the cathedral when I was walloped by an incredible wave of energy. I had never felt anything like it. It was eminating from the altar. I kept opening my eyes looking for the source of the energy. But all I could see was a box sitting on the altar.

Afterwards, still scratching my head in confusion, we did a guided tour of the adjoining museum and were told that on the altar, inside the box, were the relics (bones) of a saint.

I was shocked. I realised how powerful relics were, how they held the essense of the person and how the saint could use their relics to continue to radiate benevolent energy to the people. The greater the saint, the wider the circumference of energy they could emit.

It helped me see saints as more like enlightened beings who were working for the benefit of all beings, whether incarnated or not.

The most special day was at Basilica St Maximin where the relics of Mary Magdalene are held in a gold reliquary in the crypt. This photo is inside the main cathedral before going down a steep flight on stone steps into a small room where her skull is housed in a gold reliquary behind an iron gate.

Sitting in the presence of Mary Magdalene was a profoundly moving experience for me. The whole of the Basilica St Maximin was pulsing with her energy.

We entered the crypt and approached the gate in small numbers as it was a tiny room. I sat on the last step to connect with Mary Magdalene and basked in her presence. I would describe it like sitting in front of a furnace! Even though I sat on the bottom step a few meters away, I was being blasted by the energy pouring out of her skull.

I was overwhelmed by feelings. Mary Magdalene didn’t say much but I was filled with her energy. I offered her gratitude, love and awe. I made requests for her to accompany and guide me.

When I finally felt ready to make my way out of the crypt, I discovered I’d been down there for 30min. I was buzzing, vibrating, unable to quite enter the world again so I sat on a bench in the sun for a while to adjust and anchor the energy I had received.

It was not until the Église de la Madeleine (church of Mary Magdalene) in Paris that I discovered that the ancient pilgrims had been onto something – it was easier to connect and communicate with a saint through their relics! Here, a femur sat in its own reliquary in a side niche of the church.

It was not until the Église de la Madeleine (church of Mary Magdalene) in Paris that I discovered that the ancient pilgrims had been onto something – it was easier to connect and communicate with a saint through their relics! Here, a femur sat in its own reliquary in a side niche of the church.

Sitting there, head bent and eyes closed, I was feeling horrified that her bones had been spread far and wide. But Mary Magdalene responded that this served her, allowing her energy to be distributed so that she could affect more areas, and therefore more people.

Mary Magdalene showed me how her energy radiated outwards in a wide circumference from the church, like a stone dropped into a pond, rippling outwards until the energy of the relic’s impact dissipated.

I realised how significant a find it had been to discover her relics back in 1297 and how this would have opened up new ways to connect with Mary Magdalene.

The question is, where were the relics of Mary Magdalene kept safe during construction before the consecration of the basilica in 1316?

The Knights Templar

In 1307 the Knights Templar were arrested and during their trials they were accused of heresy and worshipping a skull or a head. These accusations were used to justify the eradication of the Order by the French king, Philip IV, and the Pope, Clement V.

In 1307 the Knights Templar were arrested and during their trials they were accused of heresy and worshipping a skull or a head. These accusations were used to justify the eradication of the Order by the French king, Philip IV, and the Pope, Clement V.

The accusations of idol worship were a key component in the suppression of the Knights Templar, allowing Philip IV to seize their wealth and dissolve the order.

While being tortured, some Templars confessed to worshipping this head. These confessions are considered unreliable by many historians due to the coercive nature of the trials.

The exact nature of the head and its significance is still a mystery. Some suggest it was a skull, possibly of John the Baptist. The Templars’ possession of various religious relics, including silver-gilt heads, may have contributed to the accusations.

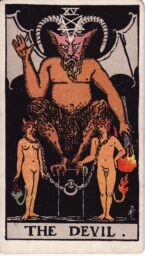

Many will be familiar with this image of the Rider-Waite Tarot deck, where the devil is based on the Knights Templar Baphomet.

The skull or a head was sometimes called Baphomet and described as a bearded head, sometimes with multiple faces. The name Baphomet is believed by some scholars to be an alteration of Mahomet (Muhammad), the founder of Islam, reflecting the Templars’ interactions with Islamic cultures during the Crusades.

The concept of Baphomet evolved over time, with later occult writers and artists, like Éliphas Lévi, developing more elaborate depictions of the figure, which became associated with occultism.

The Knights Templar, who claimed to guard the secrets of Jesus, said they possessed, and worshipped, the head or skull of God that they called Sophia or wisdom, which is the same definition as skill. A key biblical word resonant with escuele or Skill is skull (or skll with the ‘u’ removed). Accurate or not, Jesus is widely believed to have been crucified at Golgotha, the Place of the Skull. No one can say for certain what this skull is or where the Place of the Skull where Jesus was crucified is located.

Were the Knights Templar the custodians of Mary Magdalene’s relics, using her skull as a tool to contemplate death? Was this secret knowledge hidden, even under torture, with the story of Baphomet?

Considering the Templar Oath, it is easy to guess who the skull belonged to. This oath was composed by Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153) abbot and founder of the Cistercian Order. According to Anne Baring, Bernard made the Knights Templar swear allegiance to “the obedience of Bethany, the castle of Mary and Martha.”

According to Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand in ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’, castle was a womb word. Bernard essentially asked all new Templar knights to swear an oath to the womb of Mary Magdalene!

Jacques de Molay, the twenty-third and last grand master of the Knights Templar, led the Order from 1292 until it was dissolved by order of Pope Clement V in 1312.

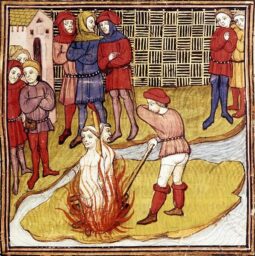

Molay was sentenced to death in 1314. On the Ile des Juifs near the palace garden, a small island in the Seine, a pyre was erected. There de Molay, de Charney, and three others of the Order were slowly burned to death. They refused all offers of pardon for retraction, bearing their torment stoically. They became revered martyrs, their bones collected from the ashes as relics.

Molay was sentenced to death in 1314. On the Ile des Juifs near the palace garden, a small island in the Seine, a pyre was erected. There de Molay, de Charney, and three others of the Order were slowly burned to death. They refused all offers of pardon for retraction, bearing their torment stoically. They became revered martyrs, their bones collected from the ashes as relics.

This image is from the Chronicle of France or of St Denis depicting Jacques de Molay being burned at the stake in 1314.

But that’s not all. The Knights Templar held secrets that made them dangerous.

The Knights Templar claimed that one of the secret founders of the Order, Godfrey of Bouillon, was a descendent of Mary Magdalene and Jesus. Not only that, the Templars were sworn to protect the bloodline of David.

In 1128 Bernard was instrumental in obtaining the recognition of the new order of Knights Templar and drawing up the rules of this new order. The Templars were essentially fighting Cistercian monks.

The Knights Templar, who claimed to guard the secrets of Jesus, said they possessed, and worshipped, the head or skull of God that they called Sophia or wisdom, which is the same definition as skill. A key biblical word resonant with escuele or Skill is skull (or skll with the ‘u’ removed).

The implication is that the French king, Philip IV, and the Pope, Clement V were not only after the material wealth of the Order but also their spiritual wealth, attempting to find and steal the relics of Mary Magdalene before they were safely reinstated in the basilica.

Did the Knights Templar burn at the stake to keep the relics of Mary Magdalene out of their hands?

How did the King Know Where to Look?

This image is of Charles II of Naples, his wife Mary and their children in the Bible of Naples, 1340.

Before the discovery of Mary Magdalene’s relics at St Baume, the church of Vézelay was strongly convinced that Mary Magdalene’s relics were there. According to history in 882 the Vezelay Abbaye sent a monk to La Sainte Baume to retrieve the remains of the saint during the Saracen invasion, out of fear that they would desecrated and destroyed.

However, in 1279, it was announced that the original crypt of Mary Magdalene was rediscovered, preserved in secret to avoid Saracen destruction. In his account, Charles II asserted the remains had never left in the first place.

So, how did Charles II of Naples know where to look?

Charles II claimed to have found the relics during a dream while imprisoned in Sicily where Mary Magdalene instructed him to find her remains. Following this dream, he oversaw excavations at the Church of Saint-Maximin in Provence, discovering her relics.

Surely it is not coincidence that although Charles II was not a member of the Knights Templar, he was a political and possibly a financial supporter, as part of the broader efforts to gain backing for their military objectives.

Surely it is not coincidence that although Charles II was not a member of the Knights Templar, he was a political and possibly a financial supporter, as part of the broader efforts to gain backing for their military objectives. Charles II was one of the European leaders that Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, met with in 1293 to gain support for the reconquest of the Holy Land. In the spring of 1293, Jacques de Molay embarked on a tour of Western Europe to garner support for the Templars’ mission of reclaiming the Holy Land.

This fresco is Mary Magdalene receives Holy Communion from an angel from San Lorenzo Maggiore in Naples.

The discovery is also linked to the earliest fresco cycles depicting Mary Magdalene’s life, which appeared in Naples, the Angevin capital, in 1295.

Why the Church Cared

Relics were big business, that attracted pilgrims who not only improved the local economy but also filled the church coffers with donations. The relics of Mary Magdalene were highly sought after as a massive drawcard that could make a church incredibly wealthy.

But it was more than just a grab for wealth.

The timing of the discovery of Mary Magdalene’s relics in fascinating. It comes before the Knights Templar were arrested for heresy and after the lengthy Albigensian Crusade against the Cathars, waged between 1209-1229.

This was the first crusade against a Christian sect, but it was more like a genocide. The Church was determined to deny Mary Magdalene’s importance and hid so much of the actual historic events.

This was the first crusade against a Christian sect, but it was more like a genocide. The Church was determined to deny Mary Magdalene’s importance and hid so much of the actual historic events.

The Cathars claimed their teachings came directly from Jesus through Mary Magdalene and the legacy of their descendants. They claimed that their teaching was descended directly from that of the Apostles and the early Church and had nothing to do with the Church of Rome. They claimed their church was as old as Rome.

The Church was determined to deny Mary Magdalene’s importance and attempted to erase actual historic events. The crusaders from the north massacred town after town, burned and destroyed evidence of Mary Magdalene’s presence in France. But the French never forgot (for more on the Cathars read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

The Cathar faith thrived alongside the Knights Templars in Languedoc. When the Order was also hounded out of extinction, secret societies sprang up throughout Europe to hold this alternate version of the story for perpetuity. The Knights Templars continued, but in secret as the Freemasons.

The teachings of Mary Magdalene spread through Europe in secret. The message is clear: her devotees were many. Mary Magdalene was viewed as leading an exemplar Christian life, more fierce and faithful than penitent, who had her own disciples, preached on an Apostolic mission in Provence, converted communities and performed miracles of healing.

So, was the skull iconography a way for artists not only to point to the discovery of her relics but of her legacy, which the Church was attempting to destroy?

But what else did the skull symbolise?

The Symbolism of the Skull

So what does a skull symbolise? And are there others who used this same symbolism?

The skull of Mary Magdalene represents penance, mortality. It symbolises her repentance, her contemplation of death, and her role as a witness to both life and death.

The skull of Mary Magdalene represents penance, mortality. It symbolises her repentance, her contemplation of death, and her role as a witness to both life and death.

As a symbol, Mary Magdalene’s skull would have been a focal point that had the power to catalyse a movement away from the Orthodox Church. The Church, having only just destroying the heretical Cathars, was intent to stop this from happening.

Mary Magdalene is by no means the first to be represented with a skull. Aside from the obvious association with the discovery of her own relics, there is also a symbolism that came to be understood.

This painting is of Saint Mary Magdalene attributed to Bartolomeo Guidobono (1654-1709).

Skulls have been used in several cultures as a good luck charm. It is believed to ward off diseases and protect the wearer from evil spirits.

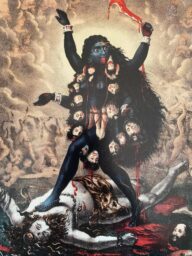

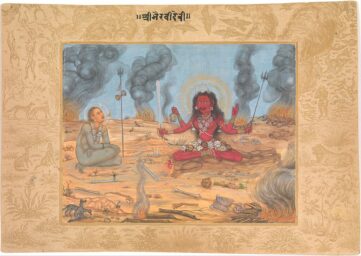

In India, the skull is clearly a symbol of death and the fear of death and is thus considered inauspicious and impure. In both Śaiva and Buddhist tantric contexts, it is a sign that the deity bearing this symbol has mastered death and has transcended the mundane world in which fear of death is nearly universal.

In Hinduism a skull necklace symbolises transformation, destruction, and rebirth. It represents the cycle of life and death, the shedding of the ego, and the ultimate liberation of the soul.

The Hindu god Shiva is often depicted with a garland of skulls (mundamala), symbolising the impermanence of life and triumph over ego. The Hindu divine mother Kali Ma is also represented with a skull necklace, known as a Mundamala, also signifies the Sanskrit alphabet, highlighting Kali’s role as the embodiment of sound and the primal syllable OM.

The Hindu god Shiva is often depicted with a garland of skulls (mundamala), symbolising the impermanence of life and triumph over ego. The Hindu divine mother Kali Ma is also represented with a skull necklace, known as a Mundamala, also signifies the Sanskrit alphabet, highlighting Kali’s role as the embodiment of sound and the primal syllable OM.

Kali, the goddess of time and change, embodies both destruction and creation.

The skull necklace represents the destruction of the old self, allowing for transformation and rebirth into a new, enlightened state.

The skulls, especially when interpreted as representing the Sanskrit alphabet, link Kali to the divine realm and the power of sound as a fundamental aspect of reality.

The skull garland symbolises Kali’s fierce and terrifying nature, representing her power and ferocity. It reflects her ability to confront evil and transform darkness into spiritual strength.

Kali symbolises the death of ego in Hinduism, Moksha (liberation from the cycle of rebirth). With the death of ego comes our authentic self. Kali is a loving and empowered mother who guides us through the transformation by dissolving all forms of time. Kali helps us tear down what needs to die inside us, like the attachments and the limiting beliefs, making room for new things and growth.

We experience true transformation in her presence as Kali brings the old cycle to an end. With her comes the divine feminine energy and change in perspective of life and death.

In some interpretations, particularly when the skull necklace is made of bone, is seen as a protective amulet, warding off negative energies and bestowing strength and courage upon the wearer.

Momento Mori

In a broader context, skull imagery, including the skull necklace, can serve as a memento mori, reminding one of the transient nature of life and encouraging a focus on spiritual growth.

In a broader context, skull imagery, including the skull necklace, can serve as a memento mori, reminding one of the transient nature of life and encouraging a focus on spiritual growth.

In the article “The Heretic Magazine”, art historian D. A. Hodgson observes “Memento mori (Latin: remember (that) you will die) is the medieval Latin Christian theory and practice of reflection on mortality, especially as a means of considering the vanity of earthly life and the transient nature of all earthly goods and pursuits.

It is related to the ars moriendi (The Art of Dying) and similar Western literature. Memento mori has been an important part of ascetic disciplines as a means of perfecting the character by cultivating detachment and other virtues, and by turning the attention towards the immortality of the soul and the afterlife.”

Although the artist is unknown, this painting is thought to be from Bologna, Italy of The Penitent Mary Magdalene.

In this theory the skull represents the embodiment of consciousness. She contemplates mortality versus immortality. The skull, symbolic of death and the afterlife points to her understanding of the transitory nature of this life, a life that must be shed to embrace everlasting life and the immortality of our soul.

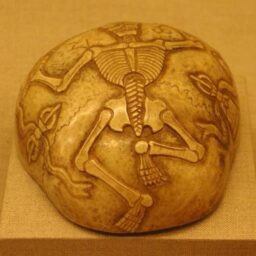

Incredibly, evidence from the Neolithic era tells us that the skull already represented the embodiment of consciousness. In ‘The Cygnus Key: The Denisovan Legacy, Göbekli Tepe, and the Birth of Egypt’ Andrew Collins notes that at Göbekli Tepe, (a settlement that existed approximately 9600- 8800 BCE) representations of human heads (separated from their bodies) the soul of a dead person, shaman, or initiate that has reached the realm of the dead under the guardianship of a supernatural vulture. The fact that the human figure is headless is a sign that the soul, in the form of a head, is no longer present, having left the body.

Incredibly, evidence from the Neolithic era tells us that the skull already represented the embodiment of consciousness. In ‘The Cygnus Key: The Denisovan Legacy, Göbekli Tepe, and the Birth of Egypt’ Andrew Collins notes that at Göbekli Tepe, (a settlement that existed approximately 9600- 8800 BCE) representations of human heads (separated from their bodies) the soul of a dead person, shaman, or initiate that has reached the realm of the dead under the guardianship of a supernatural vulture. The fact that the human figure is headless is a sign that the soul, in the form of a head, is no longer present, having left the body.

This image is of Pillar 43 at Göbekli Tepe, where animals and a headless man are depicted.

At Çatalhöyük (a settlement that existed approximately 7500-5700 BCE) a woman was buried holding a skull to her chest. This skull had been plastered and painted to look like the face of the deceased. This plastering had occurred four times.

Often, they would dig up the skulls of the dead later, plaster their faces and give them to other houses. The plaster may have attempted to recreate the faces of loved ones. Archaeologists frequently find skeletons from several people intermingled in these graves, with skulls from other people added.

Skull cult practices are seen in some different forms. Skulls drilled or engraved with stones. The first example of the behaviour performed by removing the skull of the dead body from the body in the first phase of the Neolithic period is the skulls found in Göbekli Tepe, which were regularly incised with flint and drilled to hang somewhere.

A skull from Jericho (now housed in Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) dating to around 7000 BCE had been plastered and has cowrie shells inlaid into the eye sockets.

Using Death as a Meditation

Rituals using skulls have been attested in early Indian written documents from the fifth to twelfth centuries and Tibetan texts from the eleventh all the way to the twentieth century. Skulls are multifaceted symbols in Tantric literature, simultaneously evoking both death and awakening, particularly in the Yoginī Tantras composed in India in the late seventh or early eighth century (called the Sarvabuddhasamāyogaḍākiṇījālasamvara Tantra).

Rituals using skulls have been attested in early Indian written documents from the fifth to twelfth centuries and Tibetan texts from the eleventh all the way to the twentieth century. Skulls are multifaceted symbols in Tantric literature, simultaneously evoking both death and awakening, particularly in the Yoginī Tantras composed in India in the late seventh or early eighth century (called the Sarvabuddhasamāyogaḍākiṇījālasamvara Tantra).

The use of skulls and bones are used in rituals of the Mahayoga Tantra within Vijrayana Buddhism. This includes five traditional ritual instruments made of human bones: thigh bone trumpet, Damaru, skull cup, prayer beads and bone ornaments. Tibetan ‘bone lore’, includes relics, sacred mummies and the practice of mummification in Tibet.

In the image, the Tantric goddess Bhairavi sits with her consort Shiva depicted as Kāpālika ascetics, sitting in a charnel ground. The painting is by Payāg from a seventeenth-century manuscript (c. 1630–1635), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City.

In Tantric traditions, both Buddhist (especially Vajrayana) and Hindu, skulls, often in the form of human skull cups (kapalas), used as a bowl for offerings or as a ritual implement.

These kapalas, often carved or decorated, are used as ritual objects and carry symbolic meaning, representing impermanence, the illusory nature of reality, and the transformation of negative emotions into positive wisdom.

In Vajrayana, the skull is used to symbolize the transformation of negative emotions (the three poisons: ignorance, greed, and delusion) into wisdom and compassion.

Similar to Buddhist usage, Hindu Tantra utilises skull cups (kapalas) as ritual objects. In a Hindu Tantric tradition, Kāpālika, use skulls translated as skull-men or skull-bearers.

David P. Gray in ‘Skull Imagery and Skull Magic in the Yoginī Tantras’ describes talking skulls in Tantric literature. The Buddhakapāla Yoginītantrarāja, a ninth-century text, begins with a nidāna opening passage that narrates the origin of the scripture. The text relates the death of Śākyamuni Buddha immediately following his sexual union with the yoginī Citrasenā. Although physically dead, his presence lives on via his skull, which gives a discourse. This text, then, clearly describes a skull as a “relic of the reality body”, a skull that can manifest a buddha’s gnosis.

David P. Gray gives us the account of the Tachikawa Skull Ritual, studied by Jim Sanford, where the surviving texts describes a secret method for producing a talking skull that “will tell one the secrets of the world”. This use of a skull unites the ideas of death and awakening.

In the West, we are obsessed with wanting to live forever so we try to halt time. Death is seen as the end of life with nothing to come, and so we dread and resist death. But this means we live in constant fear of death, the inevitable end to all life.

To the ancients, death was inextricably intertwined with life. Every month, the moon died and was reborn. Every winter, the sun died and was reborn. The tide came in and the tide receded.

To the ancients, death was not something to dread or even to fatalistically accept, but to embrace. They saw all around them that death was yet another creative process of renewal that brought new life. Death was seen as a needed and necessary part of transformation, the greatest of all gifts the Earth offered. The ancients innately understood that there was life in death and death in life.

This painting is by Puvis de Chavannes of ‘Mary Magdalene in the Desert’, from 1869.

We have forgotten that death is a natural part of life. As excruciating as it is, death visits us all. It is inevitable that everyone we love will die one day. To consciously witness the terrible pain, the collective and individual fathomless well of sadness, simply to hold it in the presence of divine love and compassion, requires tremendous strength and courage.

Grief is a doorway, a threshold we all pass through at one time in our lives. We are thrown into crisis, trying to grasp at an understanding of life and death – this mysterious and wonderful cycle that we are all a part of.

Mary Magdalene and a skull is such a potent symbol.

Mary Magdalene and a skull is such a potent symbol.

Mary Magdalene with her skull symbolises themes of death that so many of us are deeply uncomfortable with. But really, to face death means we can live more fully. We can honour all of Mary Magdalene’s legacy – her ministry in France and Spain, the discovery and reverence of her relics, connecting with her through her relics and contemplation of death through her skull.

So, what were the artists trying to transmit to us when they painted Mary Magdalene with a skull? Was it the secrets of her relics? The secret of her legacy in France? Was it the method of connecting with the dead through their relics? Or a way of making peace with death? I believe the skull could represent all of this and more when held in the hands of Mary Magdalene.” Excerpt from my blog: ‘What’s With the Skull, Mary Magdalene?

This painting of The Repentant Mary Magdalene from around 1660 by Luca Giordano. This is a rare depiction of Mary Magdalene actually looking at the skull, perhaps gazing into her own eyes.

Feature Image: ‘Maddalena Penitente’ by Maestro della Maddalena di Capodimonte housed in the Messina Museo Regionale.