Before Spirituality Split from Sexuality

Bridegroom, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honey-sweet,

Lion, dear to my heart,

Goodly is your beauty, honey-sweet.

Bridegroom, let me caress you,

My precious caress is more savoury than honey,

In the bedchamber, honey-filled,

Let me enjoy your goodly beauty,

Lion, let me caress you.

My precious caress is more savoury than honey.

Bridegroom, you have taken your pleasure of me,

Tell my mother, she will give you delicacies,

My father, he will give you gifts.

You, because you love me,

Give me pray of your caresses,

My lord god, my lord protector,

My SHU-SIN, who gladdens ENLIL’s heart,

Give my pray of your caresses

These are the passionate words of a lover to a king from more than four thousand years ago, in the oldest known love poem ever found. Historians say the words were recited by a bride of Sumerian King Shu-Sin (reigned 2037-2029 BCE) of Ur.

These words were passed down over generations, eventually inscribed on an eighth century BCE Sumerian cuneiform tablet small enough to fit in the palm of the hand. It was uncovered in the 1880s in Nippur, a region in what is now Iraq, and is in The Istanbul Museum of the Ancient Orient.

Long ago, spirituality was split from our sexuality, a time when women and women’s bodies were portals not only of creation but of a glimpse of the ecstasy of spiritual union. The goddess led the way and showed her followers the heights of spiritual experience they were capable of through sex.

We have forgotten what it is to use our most intimate connections as a way to god. Once long ago the ancients celebrated their love making as a sacred act. They understood it as a way to glimpse the divine, to feel themselves as soul or spirit, formless, ecstatic.

The ancients articulated this connection with explicit prayers that take our breath away. They revelled, celebrated and honoured sex. At this time, it was believed that the fertility of human, animal and plant life depended on the enactment of this ritual in a sacred place for the regeneration of the life of the goddess.

Sex was a sacred act, a vehicle to bring life into the world and because the ecstasy experienced was seen as the life of the goddess and as close as a human could get to the state of bliss of the gods and goddesses. Men and women offered themselves as the vehicle of her generative power.

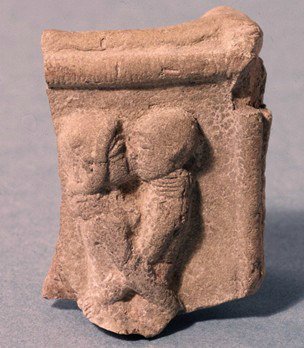

This baked clay tablet of lovers (possibly Inanna and Dumuzi) embracing is from Mesopotamia, Isin-Larsa-Old Babylonian period, (about 2000-1600 BCE) and is housed in Basel, Erlenmeyer Collection. Baked clay plaques like this were made from molds and were thus infinitely reproducible. Such plaques bearing images of deities may have been private devotional images, for they have been found in the excavation of private houses at Mesopotamian sites.

In ‘When God Had a Wife: the rise and fall of the Sacred Feminine in the Judeo-Christian Tradition’ Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince offer the best description of sacred sex rites I’ve read: “Sacred prostitution sees a priestess literally embody the goddess – it was believed, – during sexual rites either with priests or male worshippers. Although rarely described as such, this is where goddess worship becomes distinctly shamanic: For the duration of the act, the priestess is not only channelling the deity, she actually becomes the goddess. The sacred prostitute really is the sacred feminine.”

Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince go on to explain that this “was intended to be a mystical union in which the sexual ecstasy gave both participants a transcendental insight into the nature of the sacred feminine- but with emphasis on the man’s experience.”

Over my life I have been drawn inexplicably to explore the Near East. Following a fascination for Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and the eastern part of Syria) led me on a journey to understand how spirituality split from sexuality and the Divine Feminine.

To reclaim the Divine Feminine we need to go back and reread the beliefs that shaped Western culture. These beliefs live on in our cellular memory, playing out unconsciously in our beliefs and moral compass. These myths told us who we were and who we would become.

Sacred Sex

In a Mesopotamian myth ‘Inanna and the God of Wisdom’ Enki gives the Me (gifts) to Inanna. These Me includes the high priesthood, Godship, the noble, enduring crown, the throne of rulership, truth, descent into the underworld, ascent from the underworld, the art of love making, the kissing of the phallus, the holy priestess of heaven, the setting up of lamentations, the rejoicing of the heart, the giving of judgments, the making of decisions.

In a Mesopotamian myth ‘Inanna and the God of Wisdom’ Enki gives the Me (gifts) to Inanna. These Me includes the high priesthood, Godship, the noble, enduring crown, the throne of rulership, truth, descent into the underworld, ascent from the underworld, the art of love making, the kissing of the phallus, the holy priestess of heaven, the setting up of lamentations, the rejoicing of the heart, the giving of judgments, the making of decisions.

When summarising the Me, Inanna says Enki gave her the princess priestess, the divine queen priestess, the duties of the incantation priests, the noble priest and the libations priest. Inanna also states that Enki gave her the standard, the quiver, the art of love making, the kissing of the phallus, the art of prostitution and the rather ambiguous art of speeding.

This carving is of an enthroned goddess and a god, with a date palm between them. It is thought to depict Inanna and Enki. This is fromfrom Stele of Ur-Nammu. Ur, Mesopotamia from the Third Dynasty of Ur, c. 2050-1950 B.C. Lime-stone. Philadelphia, the University Museum, University of Pennsylvania. Each deity wears a multiple-horned miter crown and tiered robes, seated on a throne in the form of a temple.

In the next breath, Inanna says Enki gave her the art of forthright speech, the art of slanderous speech, the art of adorning speech, the duties of the cult hierodule and the holy tavern. Next, Inanna acknowledged the gifts of the duties of the holy priestess of heaven, described as the resounding musical instrument, the art of song and the art of the elder.

So, how do we make sense of this seemingly random list? How can we reconcile the art of love making, the kissing of the phallus and the art of prostitution in the same list with the princess priestess and the divine queen priestess? For us, sexuality is at odds with spirituality. Surely a priestess did not need to know the art of love making, the kissing of the phallus and the art of prostitution?

Inanna, Queen of Heaven

Sacred sex existed far back into the ancient Sumerian cult of Inanna and the sacred marriage rituals. In ‘The Alphabet versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image’ Leonard Shlain explains that “Inanna was the sexual partner in the Sumerians’ most important ritual – the hieros gamos, the sacred marriage.

A Sumerian king’s chief religious duty was to consummate his vows to Inanna in the sanctified wedding chamber. Through this act, eagerly anticipated by all his subjects, a king legitimised his reign. A comely surrogate, chosen from the people, ensured that the king would not be disappointed.”

The ‘Sumerian Sacred Marriage Text’ (c. 2500 BCE) whispers of feminine power we are unfamiliar with even today. Inanna/Ishtar participated in Sacred Marriage rites. Her ceremony was a ritual of sacred sexual love making. Most of the Sumerian sacred marriage texts are either love songs or descriptions of love between Inanna and her various lovers.

This clay plaque from Digdiqgah near Ur (U 17604), Mesopotamia. Isin-Lar-sa-Old Babylonian period, c. 2000-1600 в.c. Baked clay. London, The British Museum.

“My high priest is ready for the holy vulva.

My lord Dumuzi is ready for the holy vulva!…

Let the bed that sweetens the vulva be prepared!…

He put his hand in her hand, he put his hand to her heart,

Sweet is the sleep of hand-to-hand, sweeter is the sleep of heart-to-heart.” Sumerian Sacred Marriage rites (‘From the Poetry of Sumer’ by Dr Samuel Noah Kramer)

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period. It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative. The goddess legitimised dynastic rule. Sumerian sacred marriage texts can be dated to the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods (c.2100–1800 BCE), so were almost contemporary with the ceremonies.

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period. It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative. The goddess legitimised dynastic rule. Sumerian sacred marriage texts can be dated to the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods (c.2100–1800 BCE), so were almost contemporary with the ceremonies.

The prospective king asked the en-priestess to intercede on his behalf with the Queen of Heaven to allow him to enjoy “long days at her holy lap” in a great ritual. This was a very ancient ritual, going all the way back from the third to the first millennium. Royal power always required the help of goddesses.

This small clay sculpture depicts a couple entwined in love making, possibly the ancient sacred marriage rituals of the goddess Inanna and her consort Dumuzi. There are many similar pieces found from the Old Babylonian period, (c. 2000-1600 BCE), found in Ur. This is housed in the British Museum.

Presided over by Inanna, goddess of lust that allowed for sexual union rather than a mother or fertility goddess, sacred marriage gave sexuality a prominent place in cosmic order as a vital aspect of fertility. Sex is unifying and is a positive force for renewal when the male/female components are brought together.

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period. It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative.

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period. It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative.

The prospective king asked the en-priestess to intercede on his behalf with the Queen of Heaven to allow him to enjoy “long days at her holy lap” in a great ritual. This was a very ancient ritual, going all the way back from the third to the first millennium. Royal power always required the help of goddesses.

The goddess legitimised dynastic rule. Sumerian sacred marriage texts can be dated to the Ur III and early Old Babylonian periods (c.2100–1800 BCE), so were almost contemporary with the ceremonies. The Sacred Marriage ritual with all its symbolism was limited to a period of about two hundred years who adhered to the traditions of the court of Ur.

This erotic terracotta votive plaque dates to the Old Babylonian Period (c. 2000-1600 BCE).

By Babylonian times Ishtar was “Counsellor of All Rulers, She Who Holds the Reign of Kings”. On another Ishtar was “She who gives the sceptre, the throne, the year of reign to all kings”.

King Shulgi from Ur from about 2040 BCE left texts that read like the script from the annual sacred marriage. In it, he says: “Goddess, I will perform for you the rites which constitute my loyalty. I will accomplish for you the divine pattern.”

The high priestess replied: “When he has made love to me on the bed, then I in turn shall show my love for the lord, I shall make for him a good destiny, I shall make him a shepherd of the land.” In the hymn Inanna described that “by his fair hands my loins were pressed” and “he [caressed?] the hair of my lap” and “he laid his head on my pure vulva”. Although the king was identified in the sacred marriage, the woman representing Inanna was not.

The ‘Sumerian Sacred Marriage Text’ (c. 2500 BCE) whispers of feminine power we are unfamiliar with even today. Inanna/Ishtar participated in Sacred Marriage rites. Her ceremony was a ritual of sacred sexual love making. Most of the Sumerian sacred marriage texts are either love songs or descriptions of love between Inanna and her various lovers.

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period.

It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative. The prospective king asked the en-priestess to intercede on his behalf with the Queen of Heaven to allow him to enjoy “long days at her holy lap” in a great ritual.

This is thought to be Inanna and Dumuzi lying down pleasuring each other.

This was a very ancient ritual, going all the way back from the third to the first millennium. Royal power always required the help of goddesses.

Portrayed in myths, the hieros gamos was between god and goddess, between goddess and priest-king who assumed the role of the god and between god and priestess who assumed the role of the goddess.

Sacred Marriage Ritual

Sacred marriage was a potent and powerful spiritual path for the ancients, when Inanna and Dumuzi, Ishtar and Tammuz, Isis and Osiris, walked this path together. The Hieros Gamos rites were once performed annually by priestesses as the goddess and the reigning king as the god. Hieros means holy or sacred and gamos means marriage.

Sacred marriage was a potent and powerful spiritual path for the ancients, when Inanna and Dumuzi, Ishtar and Tammuz, Isis and Osiris, walked this path together. The Hieros Gamos rites were once performed annually by priestesses as the goddess and the reigning king as the god. Hieros means holy or sacred and gamos means marriage.

Sacred marriage was practised in Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Canaan, Israel, Greece, and India. The rite was consummated in a sexual or symbolic union between a Sumerian king in the role of Dumuzi and a high priestess in the role of Inanna during the ceremony.

Originally this referred only to the marriage of a god-goddess couple but was expanded to apply to symbolic marriage and cultic sexual rites. Hieros gamos came to mean the union of masculine and feminine energies, with a focus on the union of the Divine Feminine and Sacred Masculine to lead to personal transformation.

This ancient Sumerian relief is of the marriage of Inanna and Dumuzi, housed in the Louvre, Paris.

Sacred marriage is recorded in the earliest dynastic period of Sumer, around 2500 BCE, in the ‘Sumerian Sacred Marriage Text’ which whispers of feminine power we are unfamiliar with even today. The role of Inanna was performed by a priestess, who would in-personate the goddess. Towards the end of the third millennium BCE, the kings of Uruk appear to have established their legitimacy by taking on the role of Dumuzi as part of a Sacred Marriage ceremony. These rites continued until late Babylonian times in the first millennium BCE.

Throughout Sumerian documents the Kings of Sumer were mystically identified with Dumuzi and became the “beloved husband” of Inanna of Erech from the time of Enmerkar (c.2600 BCE) an En-priest at Erech, until the post-Sumerian period.

It was Inanna/Ishtar who made the king with her the high priestesses as her representative. The prospective king asked the en-priestess to intercede on his behalf with the Queen of Heaven to allow him to enjoy “long days at her holy lap” in a great ritual. This was a very ancient ritual, going all the way back from the third to the first millennium. Royal power always required the help of goddesses.

This is a balance of the left and the right hemispheres of the brain, blending the heart, spirit, and mind together into one, and revering the divine masculine and feminine forces within themselves – as well as in all of creation.

In ‘The Alphabet Versus the Goddess: The Conflict Between Word and Image’ Leonard Shlain explains that “Inanna was the sexual partner in the Sumerians’ most important ritual – the hieros gamos, the sacred marriage.

This molded baked clay tablet shows a couple making love standing up is from Isin-Larsa-early Babylonian (c.2000-1700 BCE), now in the Met Museum.

A Sumerian king’s chief religious duty was to consummate his vows to Inanna in the sanctified wedding chamber. Through this act, eagerly anticipated by all his subjects, a king legitimised his reign. A comely surrogate, chosen from the people, ensured that the king would not be disappointed.”

A Sumerian king’s chief religious duty was to consummate his vows to Inanna in the sanctified wedding chamber. Through this act, eagerly anticipated by all his subjects, a king legitimised his reign. A comely surrogate, chosen from the people, ensured that the king would not be disappointed.”

I have discussed in my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Anointrix’ that there were temples to Isis spread throughout the Mediterranean in the first century. The stories of divine couples in sacred union would have been familiar to Jesus and Mary Magdalene.

Kings enacted a ritual visitation with a goddess Sumer to Cambodia with the threat of destruction to the kingdom should the King fail in his duty. This Sacred Marriage also conferred legitimacy on their reign.

These sacred sex practices were secret to prevent them falling into the wrong hands. These practices would be dangerous if used for selfish purposes or to harm others rather than spiritual development.

These pagan sacred marriage rituals would have been very familiar to Jesus and his disciples. Was the bridal chamber rite based on these ancient rituals? Were the initiations designed to elevate the initiates into a state of sexual union where they became semi-divine?

This statue of an unidentified priestess queen is from the temple of Ishtar in the city of Mari, Early Dynastic III period (2600-2340 BCE). Again, this statue is a queen wearing a kaunakes, a flounced dress with woollen leaf petals, and skirt and a matching ceremonial shawl draped over her polos headdress, the official attire of royals.

Herodulai

The most famous priestess is Enheduanna (c. 2285-2250 BCE). Her name translates as High Priestess of An (the sky god) or En-Priestess, wife of the god Nanna and was therefore not the name given at her birth, which there is no record of. Enheduanna is remembered for a number of reasons, besides being Sargon’s daughter. She was the High Priestess of the goddess Inanna and the moon god Nanna (Sin) and lived in the most important Sumerian city-state of Ur.

The most famous priestess is Enheduanna (c. 2285-2250 BCE). Her name translates as High Priestess of An (the sky god) or En-Priestess, wife of the god Nanna and was therefore not the name given at her birth, which there is no record of. Enheduanna is remembered for a number of reasons, besides being Sargon’s daughter. She was the High Priestess of the goddess Inanna and the moon god Nanna (Sin) and lived in the most important Sumerian city-state of Ur.

Most exciting for me is that Enheduanna was the first writer whose name was recorded and the first female author. She composed beautiful heartfelt poems to Ishtar and was the first to begin writing down the myths of ancient Sumer.

This statue might be Enheduanna, High Priestess of Inanna, seated on a throne and holding a date cluster, a symbol of royalty. Her clothing proves this statue depicts a queen because only queens wore a kaunakes, a flounced dress with woollen leaf petals, and a polos headdress, the official attire of royals. The kaunakes was formal attire and were only used for ceremonial occasions, not every day.

Her throne has carved animal legs, the same type of throne used by the king on the Standard of Ur. He was a Sumerian king who defeated the king of Kish and the Akkadian allies to thus become the new King of Kish, the King of Kings, the ruler of both Sumer and Akkad.

A mosaic portrays her investiture as the new high-priestess for the temple of Dagan in Mari. A lower register of the mosaic depicts her ceremonial shawl cloth being sewn by priestesses of the temple. Next, the shawl is consecrated on the altar in the middle register. In the top register, in an image that is now missing due to damage, she wears the ceremonial shawl draped over her polos seated on her throne.

One of the titles of both Inanna and Ishtar was Hierodule of Heaven. A Greek word, Hierodule means sacred work or servant of the holy. In ‘The Myth of the Goddess: Evolution of an Image’ Anne Baring and Jules Cashford say “because of the Me and her earlier identification with the serpent wisdom of the underworld, the goddess is the bestower of wisdom and the gift of prophecy. In later Babylonian times Ishtar in her temple at Arbela was concerned with prophecy and with the interpretation of dreams: ‘To give omens do I arise, do I arise in perfectness’.”

Within the temples of Ishtar, goddess of fertility and sexuality, there were often sacred sex priestesses who provided men with a taste of enlightenment. These priestesses advertised their services by chanting in erotic hymns at the entrance to the temple. In ‘Ishtar Will Not Tire’ (translated by B. Foster 1993: 590):

Within the temples of Ishtar, goddess of fertility and sexuality, there were often sacred sex priestesses who provided men with a taste of enlightenment. These priestesses advertised their services by chanting in erotic hymns at the entrance to the temple. In ‘Ishtar Will Not Tire’ (translated by B. Foster 1993: 590):

One comes up to her – the city is built on pleasure!

“Come here, give me what I want” – the city is built on pleasure!

Then another comes up to her- the city is built on pleasure!

“Come here, let me touch your vulva” – the city is built on pleasure!

“Since I’m ready to give you all what you want” – the city is built on pleasure!

“Get all the young men of your city together” – the city is built on pleasure!

“Let’s go to the shade of the wall!” – the city is built on pleasure!

Seven for her midriff, seven for her loins – the city is built on pleasure!

Sixty then sixty satisfy themselves in turn upon her nakedness – the city is built on pleasure!

Young men have tired, Ishtar will not tire – the city is built on pleasure!

“Get on with it, fellows, for my lovely vulva!” – the city is built on pleasure!

As the girl demanded – the city is built on pleasure!

The young men heeded, gave her what she asked for – the city is built on pleasure!

Nearly 3,000 years ago ancient Assyrians composed this hymn. They were certainly not prudes. They considered sexual enjoyment a perfectly normal part of life and even thought of erotic pleasure as one of the “arts of civilization”. Female sexual assertiveness can be seen in numerous forms of art and literature in the ancient Near East, not least of all in Assyrian erotic literature that features Ishtar herself.

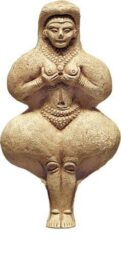

This moulded figurine of a naked woman holding her breasts is from Susa, dating between 1300-1100 BCE housed in the Louvre, Paris. Even in modern-day websites shows bias to presume these naked sexually assertive statues are prostitutes (whores).

I read that a figurine of a woman holding her breasts “has all the attributes and accoutrements of a Babylonian prostitute: She is nude and she cups her breasts. She also wears a necklace, bracelets, anklets, and several thin belts”.

I read that a figurine of a woman holding her breasts “has all the attributes and accoutrements of a Babylonian prostitute: She is nude and she cups her breasts. She also wears a necklace, bracelets, anklets, and several thin belts”.

Many sculptures of the goddess depict her holding her breasts, presenting her as a symbol of fertility. Another theory is that these may be votive objects to ask the goddess for help to become pregnant or lactation to assist breast-feeding. I personally feel her as the life-giver, as babies die without milk.

This terracotta naked woman wearing a harness with her hands clasped around her breasts is from Susa during the Medo-Elamit period (c.14th – 12th BCE).

The priestesses of Sumer were titled Hor (or in Greek Hierodulai), meaning Beloved Ones. These priestesses held a position of authority and could influence kings. Innana make it very clear she was not shy in picking lovers and promoting them to Kingship and her priestesses would have followed her example.

These priestesses were in control of their choice of lovers. They did not marry for life but had children with different kings and powerful men, securing alliances and protection for their children. The high priestess engaged in the annual Spring Equinox ritual re-enactment of the sacred marriage between Dumuzi and Innana with a young man of her choice. It was perhaps this attitude towards marriage that resulted in the meaning of Hor becoming the derogatory Whore we use today.

The priestesses who served in the temples of Inanna/Ishtar and Isis performed a sacred service to the goddess, as vehicles of her creative life in their sexual marriage with the men who came for a sacred ritual.

One of the roles of the Entu, high priestess, was to take the role of the goddess as the bride in the sacred marriage ritual. The king took the role of the god as the bridegroom, personifying the son-lover of the goddess. He was also known as the gardener.

It is possible that the children born from this ritual union were thought of as half divine, including Gilgamesh and King Sargon of Akkad (c.2300 BCE) who was the child of a high priestess and a gardener.

This suggests that the kings of Sumeria were literally the sons, consorts and fathers of the high priestesses, who personified the goddess and presided over her temple. Inanna was in possession of the Me or Laws of Civilization, giving her Wisdom.

This clay plaque of Ishtar holding a caduceus of entwined serpents in her right hand from Eshnunna, Babylonia from the early second millennium BCE. Ishtar stands in full regalia with her crown adorned with multiple horns of divinity, wearing the divine garment of flounced material. Around her neck she wears multiple-beaded necklaces. In her outstretched hand she holds the caduceus, a symbol of leadership, with her sacred animal, the lion, at her foot. Housed in the Louvre, Paris.

Another title was Nugig, a woman of high rank who played the role of Inanna in the sacred marriage. Considering Inanna rejected lovers who were unskilled, the threat of not pleasing the high priestess was real.

Another title was Nugig, a woman of high rank who played the role of Inanna in the sacred marriage. Considering Inanna rejected lovers who were unskilled, the threat of not pleasing the high priestess was real.

A Greek word, Hierodulemeans sacred work or servant of the holy. Hierodule appears as far back as the Sumerian ‘Song of Inanna’ from around 2500 BCE related to the sacred marriage of the goddess and her bridegroom the shepherd Dumuzi.

The hierodule represented Inanna as the most holy aspect of the bridal ritual. The women hierodulai were sacred, associated in New Testament times with the high priestesses of the goddesses of the ancient world.

The women hierodulai were sacred, associated in New Testament times with the high priestesses of the goddesses of the ancient world. The priestesses who served in the temples of Inanna and Ishtar performed a sacred service to the goddess, as vehicles of her creative life in their sexual union with the men who came for a sacred ritual.

I love this image of Inanna from about 2000 BCE, made of bonded stone with a marble base, it is 29 cm (11.5 inches) high. Inanna is the goddess of love, beauty, sex, violence, and justice. Inanna was strong, powerful and sexually active. Rather than waiting to be chosen she chose. Inanna had sex for love and for enjoyment.

Christian religious guilt has made the body something to be ashamed of, to doubt and distrust. We were separated from the divine, told that our bodies were cursed and that sex was something to be ashamed of.

We need to welcome sexuality back into our spirituality. We need to embrace our humanness and honour our deep need for closeness and connection, affection, intimacy and deep pleasure. The path to wholeness means we need to strip away all the lies and illusions we ever thought about ourselves.

Fired clay mould for nude figure of Ishtar, with hands at breasts and a horned crown, wings or cloak and talon feet. Clay mould. Old Babylonian period.

We have forgotten how to use sex as a sacred act, a vehicle to bring life into the world. Through ecstasy we can experience the life of the goddess and be as close as a human can be to the state of bliss of the gods and goddesses.

Women are sensual, sexual beings who generate the creative activity for the world to multiply. Women are sovereign of their own body, mind, emotions and soul. Women can be outraged and lustful, violent and passionate. Women are are free to explore the full spectrum of our physical, mental, emotional and spiritual beingness.

By reclaiming our sacred sexuality, we remember the power and authority that lies dormant within our bodies, ready to rise once more. We celebrate our sensual aliveness and reframe sex as an act of devotion.

There is so much compelling evidence that Jesus initiated Mary Magdalene into this, the highest initiation he offered, I’ve written a separate blog about it…

And why this initiation was so vehemently suppressed by the Orthodox Church. (for more read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene and Sacred Union’).

Featured image: clay plaque from Isin-Larsa, Mesopotamia during the Old Babylonian period (c. 2000-1600 BCE) now housed in the British Museum. This damaged terracotta bed holds two figures in a passionate embrace, kissing. Each wraps one hand about their lover’s neck and the other around the waist, in gestures evocative of deep human emotion. The scene’s ritual rather than secular nature is suggested by the baldness of the male figure. Similar shaven heads are believed to characterise priestly or royal figures.