Mary Magdalene, the Anointrix

You could be forgiven for presuming anointing are ancient forgotten rituals that do not hold power in our world. But did you watch the coronation of King Charles in 2023? The whole ceremony was televised apart from one moment: the anointing.

This anointing ritual, also known as the Act of Consecration, was so sacred it was kept off camera, a solemn private ritual not for the masses’ consumption. The anointing is the most sacred part of the ceremony.

Ian Bradley in ‘God Save the King: The Sacred Nature of the Monarchy’ writes that this anointing was based on the anointing of King Solomon. Incredibly, ceremonies and rituals performed for the British monarchy are based on practices described in the Old Testament.

Within the coronation service, the anointing of the new monarch with holy oil is directly based on the anointing of the earliest Israelite kings as described in the first book of Samuel and the first Book of Kings.

Bradley explains: “The act of anointing, which was usually carried out by a priest, signified the setting a part of the king and signalled his divine election. It was also the moment at which God adopted the monarch as his son and at which God’s spirit descended on him. As an act of consecration and setting aside, the anointing of kings was in many ways comparable to the ordination of high priests.”

King Charles was covered with a canopy, traditionally held by four Knights of the Garter. He is seated in King Edward’s chair (also called the Coronation chair), with the Stone of Scone (the stone used to crown kings in Scotland, stolen in the thirteenth century and taken to London) beneath him, while the choir sing “Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet”, referencing Solomon’s coronation.

King Charles was covered with a canopy, traditionally held by four Knights of the Garter. He is seated in King Edward’s chair (also called the Coronation chair), with the Stone of Scone (the stone used to crown kings in Scotland, stolen in the thirteenth century and taken to London) beneath him, while the choir sing “Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet”, referencing Solomon’s coronation.

King Charles was anointed with holy oil on the palms of his hands, his chest, and his head using oil consecrated in Jerusalem at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

During the anointing, the Archbishop of Canterbury says: “Be your hands anointed with holy oil. Be your breast anointed with holy oil. Be your head anointed with holy oil, as kings, priests, and prophets were anointed. And as Solomon was anointed king by Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet, so may you be anointed, blessed, and consecrated King over the peoples, whom the Lord your God has given you to rule and govern; in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.”

An Anointrix

What does this have to do with Mary Magdalene?

What does this have to do with Mary Magdalene?

Some say Mary Magdalene is a High Priestess of Isis or an Anointrix. But when we dig deeper is this what she was historically? Or is this a modern overlay of an archetype?

So, what can be proven about Mary Magdalene?

Reading the New Testament it’s not surprising that one of Mary Magdalene’s icons is the alabaster jar of perfumed oil. She is associated with anointing over and over.

Once the anointing of a king was not performed by a man. This and other anointing rituals were the role of a woman trained as an anointrix.

This painting of Mary Magdalene clutching her jar to her breast is by Giacinto Brandi (1621-1691). She has a halo, while her eyes gaze longingly heavenwards.

I believe Mary Magdalene was most likely an ordained priestess, a prophetess, a mystic, a powerful preacher and an initiator who performed baptisms. Mary Magdalene continued her own ministry after the crucifixion who preached Jesus’ message in Gaul (France) and Spain.

Clear evidence of priestess training are the anointing rituals she performed for Jesus as an anointrix. An anointrix is a woman who performs rituals. She would have been a highly trained priestess.

According to the Jewish Civil Law, there were specific ritual when an anointing was performed. Expensive oils were used for marriages, coronations, and burials. These rituals were performed to anoint a new king, a husband and at the death of that husband.

Anointing may have been a core practice of Mary Magdalene that Jesus began to include in his own initiations.

In ‘Mary Magdalene: A Biography’ historian Bill Chilton believes that anointing was something that Mary Magdalene taught Jesus, as she came from Galilee, a region where healing and shamanic arts were well known.

We do know that Jesus introduced anointing into his five sacraments, as detailed in the ‘Gospel of Phillip’ (For more read my blog: ‘The Five Sacraments’).

Symbol of the Jar

Before we dive deep into the descriptions of anointing rituals in the Gospels, we need to have an understanding of the symbolism of the jar.

The jar became a key symbol of Mary Magdalene in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries. The ointment jar became a standard attribute in Renaissance and later depictions, solidifying its place in her iconography.

The jar’s form varied, sometimes depicted as a box, flask, pot, or ointment cup, but its association with Mary Magdalene remained consistent. The jar represents the ointment she used to anoint Jesus’ feet, highlighting her repentance and devotion.

In ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’ Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. they explain Mary Magdalene’s alabaster anointing jar as an ancient symbol.

This Penitent Magdalene by Dolci, Carlo, painted around 1650- circa 1651, depicts her once more with the sole symbol, the jar. The jar is in the focal point of the painting, lit up along with her hand and face.

The anointing jar was used to symbolise the sacred womb elixirs. All sacred vessels symbolised “the multidimensional feminine womb, source of the waters of life, source of magic, and source of conception, creation and rebirth.”

An empty vessel has always signified the womb and its procreative powers to create life. The jar in Mary Magdalene’s hands was a symbol of this also, hinting at her and Jesus’ offspring, who most probably grew up in Gaul (France).

In ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’ Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. explain: “The shape and form of the sacred vessel varied over time and culture but its magical essence and symbolic power has remained constant. It was the Sacred Basket, the Holy Grail, the Sacred Gourd, the Sparkling Chalice, the Sacred Cup, the Sampo of the Fins, the gold and silver libation vessels of the Temple of Jerusalem, the carved stone dragon and lion flasks of Sumeria, the cup of the derflaith, the dragon drink of Sovereignty of the Celts, and an infinite variety of others. The sacred vessel was not merely symbolic; it was the everyday magical tool essential to the priestesshood.”

In ‘Magdalene Mysteries: The Left-Hand Path of the Feminine Christ’ Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. explain: “The shape and form of the sacred vessel varied over time and culture but its magical essence and symbolic power has remained constant. It was the Sacred Basket, the Holy Grail, the Sacred Gourd, the Sparkling Chalice, the Sacred Cup, the Sampo of the Fins, the gold and silver libation vessels of the Temple of Jerusalem, the carved stone dragon and lion flasks of Sumeria, the cup of the derflaith, the dragon drink of Sovereignty of the Celts, and an infinite variety of others. The sacred vessel was not merely symbolic; it was the everyday magical tool essential to the priestesshood.”

Mary Magdalene and other myrrhophores or ‘myrrh bearers’, carried myrrh and frankincense oils traditionally for anointing rites at birth, death, rebirth, kingship, queenship, investiture in the priesthood, and sacred marriage.

Seren Bertrand and Azra Bertrand M.D. believe “This precious alabaster jar, and the secrets it holds, has been passed down, metaphorically, by many lineages of priestesses, housing the fragrance of their rites.”

This painting of Mary Magdalene is by Luca Signorelli.

Priestess of Isis

Many believe the anointing rituals Mary Magdalene performed prove she was a Priestess of Isis. (For more on Isis read my blog: ‘Goddesses of Egypt’).

Many believe the anointing rituals Mary Magdalene performed prove she was a Priestess of Isis. (For more on Isis read my blog: ‘Goddesses of Egypt’).In lineages influenced by Egypt, the Essenes, and early Christian mystery schools, Mary Magdalene is seen as a High Priestess of Isis, trained in temple arts of anointing, healing, and sacred sexuality.

After conquering territories of the Mediterranean, Alexandra the Great installed rulers left in each region to rule in his stead, the Greek culture and beliefs swept through, shifting ancient beliefs and religions.

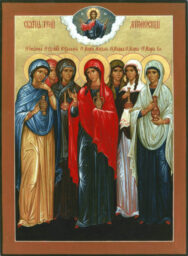

This icon depicts the Holy Myrrhbearing Women from the Damascene Gallery.

In the Hellenistic period (323–30 BCE), when Egypt was ruled and settled by Greek Ptolemaic dynasty, Isis was worshipped by Greeks and Egyptians, along with a new god, Serapis.

The Hellenistic mystery religion of Alexandria spread throughout the Roman Empire with their troops. This was a mix of Egyptian iconography, Greek philosophy, Mesopotamian cosmology and Roman ritual form.

The cult took the religion out of the Pharaonic temples and into the sphere of everyday people. The cult’s appeal originated from its promise of personal salvation and available to all walks of life. It led to its eventual acceptance and even patronage by some emperors, such as Caligula and Vespasian.

The cult of Isis evolved into a mystery religion, characterised by secret initiations, elaborate rituals, and a focus on personal salvation and protection.

This Hellenistic mystery religion was a spiritualised mystery school where initiates underwent symbolic death and rebirth in private rites. The cult’s popularity was boosted by traveling soldiers and traders, who helped disseminate its practices and beliefs across the empire.

As Hellenistic culture was absorbed by Rome in the first century BCE, the cult of Isis became a part of Roman religion. The cult of Isis attracted followers from all levels of Roman society, including women, children, slaves, freedmen, and even members of the imperial family.

What Do We Know About the Isis Cult?

The Romans adapted the cult, placing less emphasis on the maternal aspects of Isis and focusing more on her role as a protector, a bringer of victory, and a bestower of wealth.

The cult had both public displays, like processions and festivals, and private, secret rituals that were performed within the temples. The cult presented Isis as a powerful, universal goddess who offered protection, hope, and salvation to all who sought her favour.

The cult revolved around the story of Osiris’s death and resurrection, a powerful narrative of death, loss, and rebirth. Initiation into the cult involved secret rituals and a promise of personal salvation and connection with the divine.

A fresco in the Temple of Isis at Pompeii from the first century CE depicts a ceremony worshipping the sarcophagus of Osiris. The death of Osiris was a prominent motif in the cult of Isis. The sarcophagus’s appearance here may refer to the emphasis on Osiris and the afterlife found in the mysteries dedicated to Isis.

The devotees of Isis were a small proportion of the Roman Empire’s population but were found all across its territory. Her following developed distinctive festivals such as the Navigium Isidis, as well as initiation ceremonies resembling those of other Greco-Roman mystery cults. Some of her devotees said she encompassed all feminine divine powers in the world.

The mysteries aimed to strengthen a devotees’ commitment to Isis and potentially ensure a blessed afterlife. According to the World Atlas, first century CE initiation into the Mysteries of Isis involved purification rituals, symbolic death and rebirth experiences, and potential visions from the goddess. While not explicitly detailing anointing, these rites included symbolic acts and forms of purification like wearing linen, fasting and ritual bathing, possibly in sacred waters, to cleanse themselves physically and spiritually.

The mysteries aimed to strengthen a devotees’ commitment to Isis and potentially ensure a blessed afterlife. According to the World Atlas, first century CE initiation into the Mysteries of Isis involved purification rituals, symbolic death and rebirth experiences, and potential visions from the goddess. While not explicitly detailing anointing, these rites included symbolic acts and forms of purification like wearing linen, fasting and ritual bathing, possibly in sacred waters, to cleanse themselves physically and spiritually.

Initiation often involved a period of darkness, representing spiritual death, followed by a symbolic rebirth into a new spiritual identity within the cult.

Was Mary Magdalene initiated into the Isis Mysteries?

Probably. By the first century CE when Magdalene lived, the cult of Isis in ancient Egypt had evolved as it gradually spread to the Greek world before reaching Rome. Mystery Schools to Isis could be found everywhere. There was even a Temple to Isis in Rome (the first of many was constructed in 43 BCE). Although there is no evidence of a dedicated temple to Isis in Canaan, Egypt was not that far away.

Probably. By the first century CE when Magdalene lived, the cult of Isis in ancient Egypt had evolved as it gradually spread to the Greek world before reaching Rome. Mystery Schools to Isis could be found everywhere. There was even a Temple to Isis in Rome (the first of many was constructed in 43 BCE). Although there is no evidence of a dedicated temple to Isis in Canaan, Egypt was not that far away.

Mary Magdalene could easily have spent years in Egypt, studying the rites of Isis. But this is almost impossible to prove. All we can do is read between the lines in the stories where she is mentioned. But I can’t find evidence that this proves that she gained her skills as an Anointrix through a Temple of Isis training.

In Alexandria, Egypt, I saw second century CE Roman statues of priestesses of Isis holding a situla (bronze jug) or cista (ritual basket), although these may be statuesa of Isis.

Could these anointing rituals be part of Jewish customs?

Let’s take a quick look at the descriptions of anointing rituals in the New Testament…

The Unnamed Woman

The most memorable anointing ritual is curiously all four gospels (Matthew 26:6-13; Mark 14:3-8; Luke 7:36-47; John 12:1-8), describing an unnamed sinful woman expressing her “great love” of Jesus by anointing “his feet weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them.” (Luke 7:38).

The most memorable anointing ritual is curiously all four gospels (Matthew 26:6-13; Mark 14:3-8; Luke 7:36-47; John 12:1-8), describing an unnamed sinful woman expressing her “great love” of Jesus by anointing “his feet weeping, she began to wet his feet with her tears. Then she wiped them with her hair, kissed them and poured perfume on them.” (Luke 7:38).

This caused an uproar amongst the disciples, who took exception to her uninvited arrival, the waste of such an expensive ointment, her emotional outpouring, and most likely the implications of ritual her performing the anointing ritual.

We are not going to explore how unconventional and courageous her actions were to be known as a sinner (For more on this read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Rebel’).

There was a lot of information implied in this one event that the Church would have been deeply uncomfortable with.

This fresco of Christ in the House of Simon is from the mid-fourteenth century in the Decani monastery, Serbia.

Who was this Unnamed Sinner?

Only in the Gospel of John is her name given. In the Gospel of John Jesus is visiting his “friend” Lazarus. The woman who anoints Jesus’ feet is identified as the sister of Lazarus, Mary of Bethany:

Only in the Gospel of John is her name given. In the Gospel of John Jesus is visiting his “friend” Lazarus. The woman who anoints Jesus’ feet is identified as the sister of Lazarus, Mary of Bethany:

“Now a certain man was sick, named Lazarus, of Bethany, the town of Mary and her sister Martha. (It was that Mary which anointed the Lord with ointment, and wiped his feet with her hair, whose brother Lazarus was sick” (Gospel of John 11:1-2).

This clears up the confusion between the names. Mary Magdalene is Mary of Bethany who is the unnamed, sinful woman who anointed Jesus.

The gospel writers attempted to obscure the connection between Mary Magdalene’s presence at Bethany and her presence in the garden of the resurrection.

This depiction of ‘Jesus at the home of Mary and Martha’ is by Harold Copping (1927) is an illustration from ‘Women of the Bible’.

Placing her at the forefront of these pivotal events placed both her and the ritual of anointing gave Mary Magdalene way too much spiritual authority. This served to reduce her claim to apostolic legitimacy, and as Apostle to the Apostles.

What’s in a Name?

Why did her name change from Mary of Bethany to Mary of Magdala and Mary Magdalene? My personal theory is that Jesus gave her the title Magdalene. He gave his other disciples nick names and titles, so why not Mary? (For more read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Rebel’).

“The names of the twelve apostles are these: first, Simon, who is called Peter, and Andrew his brother; James the son of Zebedee, and John his brother” (Matthew 10:2) and “James the son of Zebedee and John the brother of James (to whom he gave the name Boanerges, that is, Sons of Thunder)” (Mark 3:17).

This portrait by Giampetrino, probably Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, was a north Italian painter of the Lombard school and Leonardo da Vinci’s pupil, active 1520-40. I love how this slight smile suggests she knows more than she’s letting on. She holds her jar of anointing oil, keeping its secrets hidden from the uninitiated and uneducated.

What I love about depictions of Mary Magdalene with the jar is the expression on her face. It is as if she’s taunting us, challenging us to lift the lid and look within. Her expression warns that we might not like what we find inside. She says to us “open if you dear” with her eyes.

Mary Magdalene was an Anointrix or Myrrophore – someone trained to us sacred oils for anointings.

According to the legends of France, Mary Magdalene is Mary of Bethany, sibling to Lazarus and Martha. They know this because Mary Magdalene arrived on the shores of Gaul (France) after the crucifixion accompanied by her siblings Lazarus and Martha. (For more read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

So why was this event so important that all four gospel writers were forced to include it?

Because the anointing of Jesus was so uncomfortable for the writers of the gospels her name was omitted to conceal her identity.

Why?

Anointing her Husband

So, why did the Gospel writers want to conceal the identity of the anointrix?

So, why did the Gospel writers want to conceal the identity of the anointrix?

Why did they not want future generations to know that Mary Magdalene had performed the anointing ritual?

Imagine how awkward would it have been for the Church if it was clear that Mary Magdalene was anointing her husband…

In the Gospel of Philip and the Gospel of Thomas discovered in 1945 at Nag Hammadi, sheds light on the truth of their relationship. These texts describe Mary Magdalene as koinonôs of Jesus.

The Greek word koinonôs has the explicit meaning of close companion or consort and refers to a wedded and intimate sexual partner.

This painting, ‘St. Mary Magdalene’, from 1524 is by Bernadini Luini or Andrea Solario, housed in The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, USA.

In a translation of the ‘Gospel of Philip’ by Jean-Yves Leloup, the nature of Jesus’ relationship with Mary Magdalene is described:

“There were three who always walked with the Lord …his sister and his mother and his consort (koinonôs) were each a Mary. (These three women were at the crucifixion and also at the sepulchre). And the companion (koinonôs) of the Saviour is Mary Magdalene.”

According to Jean-Yves Leloup in ‘Sacred Embrace of Jesus and Mary’ koinonos means fiancé, spouse or companion, and signified a woman who was both wife and spiritual partner. This turn of phrase that they “were each a Mary” makes it sound like this was not a name by a title.

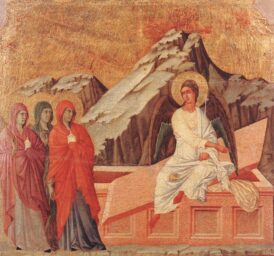

This depiction of the resurrection of Jesus is a fourteenth century work by Duccio di Buoninsegna of the ‘Three Marys” (including Salome identified as Mary Salome). Clutching their ointment jars to the chest, the pull back in surprise and fright as they discover Jesus, alive, seated nonchalantly on top of his tomb.

But there is more: Christ loved her more than the disciples and used to kiss her often on her mouth. The rest of the disciples were offended by it and expressed disapproval. They said to him, ‘Why do you love her more than all of us?’ The Saviour answered and said to them, ‘Why do I not love you like her? When a blind man and one who sees are both together in darkness, they are no different from one another. When the light comes, then he who sees will see the light, and he who is blind will remain in darkness.’”

Rather than the conventional marriage, sanctified and recognised by the law, koinonôs signifies a different type of relationship that is not based on the usual societal expectations.

In ‘When God Had a Wife: the rise and fall of the Sacred Feminine in the Judeo-Christian Tradition’ Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince theorise that although Jesus and Mary Magdalene were in a relationship, they were not legally married. Judaic custom meant all men were married by twenty at the latest so Jesus must have been married to someone else, separated, or widowed.

This marriage would make Mary Magdalene a dynastic wife. The train of thought goes that Mary Magdalene was descended from King Saul of the tribe of Benjamin. Jesus, on the other hand, is descended from King David of the tribe of Judah.

This marriage would make Mary Magdalene a dynastic wife. The train of thought goes that Mary Magdalene was descended from King Saul of the tribe of Benjamin. Jesus, on the other hand, is descended from King David of the tribe of Judah.

This makes their marriage a dynastic union reuniting two houses of Israel. This would explain why the apostles wanted to obscure the identity of Mary Magdalene and her relationship with Jesus.

This theory was first popularised by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh and Henry Lincoln in ‘The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail’ and copied by Dan Brown in his wildly successful ‘The Da Vinci Code. The authors believe they found evidence that Mary of Bethany was married to Jesus.

This painting of Jesus and Mary Magdalene looks like a contemporary depiction but it was actually painted in 1520 by Lucas Cranach, housed in Friedenstein Castle in Gotha, Germany.

There were two stages to dynastic marriages. After betrothal the couple was given a trial period of three months of confinement to determine whether they could conceive. Even if the woman conceived during this initial three months, she was still considered an almah or virgo until the three months was completed.

If the period was unsuccessful in producing a child another noble woman would be selected and the process begun again. The first century ‘Wars of the Jews’ reports that couples were given a trial period of three years of wedlock in dynastic order.

Marriage was celebrated only after the second stage was completed successfully and a ceremony conducted. Only then was she considered a wife and be blessed by the Zadok priest.

Anointing a King

Jesus was given the titles Christ, meaning the anointed one in Greek, and Messiah, meaning literally anointed, which refers to a ritual of consecrating.

Jesus was given the titles Christ, meaning the anointed one in Greek, and Messiah, meaning literally anointed, which refers to a ritual of consecrating.

But who and when was this ritual performed?

Legend tells us that The Unnamed Woman used spikenard. Using spikenard means this Messianic anointing is a bridal event rather than installing a king that would have been performed by a Zodak priest.

As a Syrian, Mary Magdalene had much in common with the Song of Songs bride, who also used spikenard: “Then Mary took about a pint of pure nard, an expensive perfume; she poured it on Jesus’ feet and wiped his feet with her hair. And the house was filled with the fragrance of the perfume” (John 12:3).

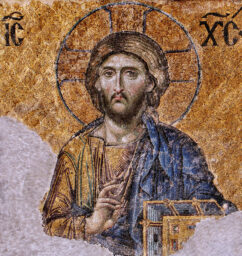

This is a mosaic of ‘Christ Pantocrator’ from Hagia Sophia, Turkiye.

Compare this with Song of Songs: “While the king was at his table, my perfume spread its fragrance” (Song of Songs 1:12). The rite performed in the Song and repeated by Mary Magdalene is an ancient rite of a bride sanctifying her bridegroom’s meal.

The nuptial anointing ritual was the express privilege of a Messianic bride performed solely at the First and Second Marriage ceremonies. Mary Magdalene could only anoint both his head and feet with sacred oil if she was the wife and a priestess in her own right.

Priestesses performed sensual anointing rituals that gave a man his kingship or they anointed those who were about to die or receive spiritual initiation. The story of Mary Magdalene anointing Jesus is of vital importance as it points towards their partnership as the priestess bride anointing the sacrificial priest-king.

In ‘Mary the Magdalene Legacy’ Laurence Gardiner believes that this sacred anointing was inherited from the Mesopotamian traditions of Inanna and Dumuzi with the Hieros Gamos of the shepherd-king. (For more on Inanna and Dumuzi read my blog: ‘Goddess of Mesopotamia’).

Laurence Gardiner suggests: “This was an ancient princely culture of Mesopotamian Sumer as a representation of the goddess bestowing favour and kingship on her chosen bridegroom.”

This adds them to the other couples throughout the Middle East who performed the same rite: Inanna and Dumuzi, Astarte and Ba’al, Isis and Osiris, Venus and Adonis.

This adds them to the other couples throughout the Middle East who performed the same rite: Inanna and Dumuzi, Astarte and Ba’al, Isis and Osiris, Venus and Adonis.

References to an anointing rite of the new king with oil is in the Song of Songs (1:12) with the celebration of the bride and bridegroom. Later, Hebrew male prophets and priests usurped the role of the priestess-queens and took on the right to anoint the kings of Israel.

Jesus saw all the love that she had poured into this ritual anointing. He knew himself anointed as the messiah in preparation for his final trial. They were united in this act of devotion and of love. He heard all she could not express in front of the disciples. He saw her, his bride, sacrificing their love for the benefit of all.

Anointing Before Burial

In ‘Mary Magdalene: A Biography’ historian Bill Chilton succinctly summarises: “She connects his death and Resurrection”. At Bethany, Mary Magdalene anoints him to prepare him for the cross. On Easter morning Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb with her spices and perfumes to anoint his body for death.

In ‘Mary Magdalene: A Biography’ historian Bill Chilton succinctly summarises: “She connects his death and Resurrection”. At Bethany, Mary Magdalene anoints him to prepare him for the cross. On Easter morning Mary Magdalene arrives at the tomb with her spices and perfumes to anoint his body for death.

Mary Magdalene is pivotal to the events, performing the anointing rituals and foreshadowing the events to come.

The final anointing ritual was for a corpse prior to entombment. Jesus understood the intent behind the anointing ritual performed by Mary Magdalene.

Jesus understood the unspoken message, saying: “She is come aforehand to anoint my body to the burying” (Mark 14:8).

This painting is of The Three Marys at the Tomb by Mikołaj Haberschrack, from about 1470.

Jesus turned to his outraged disciples, saying to them, “Why are you bothering this woman? She has done a beautiful thing to me. The poor you will always have with you, but you will not always have me. When she poured this perfume on my body, she did it to prepare me for burial. Truly I tell you, wherever this gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her” (Matthew 26:10-13).

Under Jewish civil Law everyone, even the most despised criminal, had to have a proper burial to save the land from being defiled. To that end, there were strict procedures for the disposal of bodies, which had to be laid in tombs by sunset on the day of death.

The normal practice of anointing before a burial would have been to wash, perfume and bind the body so that it wouldn’t smell in the heat at the funeral seven days later.

This was a laborious procedure which could take up to twenty-four hours. It was governed by religious custom and by a powerful sense of respect for the body.

According to Jewish tradition, only his mother, his sister or his wife would be allowed to anoint his body after the crucifixion. If Mary Magdalene was only one of his close followers, she would not have been admitted to the tomb to dress his body.

But in the Gospel of John (20:15), Mary Magdalene had the right to claim the body of Jesus for burial. Mary Magdalene would have needed to be a close female relative or next of kin.

The fact she went to the tomb to anoint Jesus’ body means that she must have been his wife as she was of the highest standing, higher even than his mother.

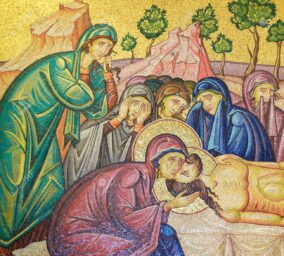

This image is a wall mosaic of Christ’s body being prepared after his death, opposite the Stone of Anointing, in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

What The Church Tried to Conceal

This story of the unnamed sinner who anoints Jesus survived the test of time. It is a powerful and profound anointing ritual performed by Mary Magdalene in her role as anointrix.

This story of the unnamed sinner who anoints Jesus survived the test of time. It is a powerful and profound anointing ritual performed by Mary Magdalene in her role as anointrix.

But the woman, stripped of her name, has lost her identity, her authority and her power within the story.

We have been deprived of truly knowing what “she hath done” so we are left in the dark and cannot fathom what this story was meant to celebrate.

We cannot truly honour this episode “told in memory of her” when we are not given the full story. This story, with its protagonist’s name removed, loses all its impact and is given to us strangely lacking a punch line. It feels incomplete.

This painting of Mary Magdalene by Jan van Scorel (Rijksmuseum Amsterdam version) is dated around 1530.

Removing her identity strips the context to the story. I feel like we are missing something vital, like an element of the story has been removed, stripping it of its true meaning. And that’s because it is stripped of the most meaningful details. Her name. Her identity.

Why was it so important to conceal her identity?

Well, the Orthodox Church spent hundreds of years telling the people that Jesus was semi-divine and was unmarried and not a father, justifying enforcing celibacy on clergy.

It also helped the Church to reduce the power and authority of women in the Church, gradually excluding them from any active roles.

Having a powerful and potent woman leader of a ministry was deeply unsettling and would undermine the assertion of the Church that women were inferior and not worthy of positions within the Church.

Having a powerful and potent woman leader of a ministry was deeply unsettling and would undermine the assertion of the Church that women were inferior and not worthy of positions within the Church.

But the artists of the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries were having none of it. They clearly put the ointment jar back into her hands, clearly identifying her as an anointrix.

The jar became a standard attribute in Renaissance and later depictions, solidifying its place in her iconography.

This rather painting of Mary Magdalene with an Ointment Jar is attributed to the Master of the Mansi Magdalene (1490-1530) depicts her clutching her hair, draped around her chest and waist but revealing a cheeky breast. Beside her right hip, a forgotten jar sits neatly in view. After all, what could she possibly have to hide?!

Even though the Church did not uphold the intention of their Messiah, the Gnostic Gospels tell us that Jesus’ words continued to ring through the centuries, telling his followers “Truly I tell you, wherever this gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her” (Matthew 26:13).

How did they know? How were these artists so sure of her identity and courageous enough to go against the Church?

Perhaps this is yet another example of the underground organisations of the surviving Cathars and Knights Templars of France disseminating secret information throughout Europe.

This was not just a story of Mary Magdalene’s role as an anointrix, as a trained and skilled priestess performing anointing rituals, but reveals the very nature of who Mary Magdalene was and her relationship with Jesus.

This is what the Church tried – unsuccessfully – to conceal.

Feature Image: Saint Mary Magdalene by Giampietrino, c. 1521, tempera on wood, Gift of The Samuel H. Kress Foundation.