Mary Magdalene, the Fallen Woman

“From sinner, to preacher, to contemplative, to saint, Mary Magdalene is associated with miracle cures; assistance at childbirth; raising the dead; and freeing the imprisoned. However, the most enduring detail is always her sin.” ~ Hetta Howes

Most of us have been told that Mary Magdalene was a reformed prostitute or a woman with loose values, who was saved by Jesus and forgiven for her sins. This perspective emphasises her redemption, hope, and her role as a symbol of grace. She became known as the penitent fallen woman and was the story of redemption that even the most sinful woman could aspire to.

But what if this was a myth created by the Catholic Church that had no basis in history?

To understand, we need to go back to the deterioration of the relationship between Mary Magdalene and the Orthodox Church. After Jesus’ crucifixion, Jesus chose Mary Magdalene to be the Apostle to the Apostles when he appeared to her first.

To understand, we need to go back to the deterioration of the relationship between Mary Magdalene and the Orthodox Church. After Jesus’ crucifixion, Jesus chose Mary Magdalene to be the Apostle to the Apostles when he appeared to her first.

The ‘Gospel of Mary’ describes Jesus commanding her to announce his resurrection from the dead. Mary Magdalene asks the disciples to spread word of the resurrection.

But the disciples were incredulous that Jesus chose to appear to her, a woman. They lashed out jealously. Mary Magdalene is called a heretic and liar for the “strange teaching” she described. The disciples could not even contemplate the message she shared with them and the spiritual map that had been gifted to Mary Magdalene alone.

This marks the souring of the relationship between Mary Magdalene and the male disciples.

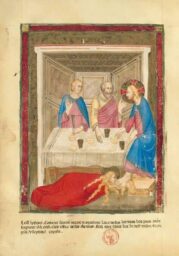

This image of ‘Mary Magdalene Announcing the Resurrection to the Apostles’ has miraculously survived from an Illumination on parchment dating around 1123 from St. Albans Psalter, St Godehard’s Church, Hildesheim.

Erased from Codified Scriptures

In the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 CE her ministry was removed by the newly founded Orthodox Church. By this time, there were hundreds of Gnostic Christian groups, each with their different beliefs. One group in particular, the Arians, were causing conflict. They believed that Jesus was not divine but a created being. Arianism and many other groups were branded heretical. It is also this First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in the year 325 CE that the word Cathari was used (see blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

In the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 CE her ministry was removed by the newly founded Orthodox Church. By this time, there were hundreds of Gnostic Christian groups, each with their different beliefs. One group in particular, the Arians, were causing conflict. They believed that Jesus was not divine but a created being. Arianism and many other groups were branded heretical. It is also this First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in the year 325 CE that the word Cathari was used (see blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

This image is the Council of Nicaea in 325, depicted in a Byzantine fresco in the basilica of St. Nicholas in Demre, Türkiye.

This council was a conclave of over three hundred Christian bishops, priests and acolytes. These were leaders from every part of the ancient world including Spain, France, Egypt, Persia, Syria, Armenia and Israel. carefully chosen by Emperor Constantine who trusted to codify their religion his way.

The council aimed to establish a unified doctrine of faith for the Orthodox Church. The council sought to resolve a dispute over the nature of Jesus – human or divine – and his relationship with God the Father. The council decided that Jesus was said to be “begotten, not made”, asserting that he was not a mere creature, brought into being out of nothing, but the true Son of God, brought into being “from the substance of the Father”.

The council declared that Jesus is “true God from true God, Light from Light”. This meant affirming that Jesus was not created but rather eternally begotten by the Father, co-equal with him in essence (consubstantial). This was enshrined in the Nicene Creed, a statement of faith still used in many Christian traditions today.

The council banned Gnostic cults, including Arianism, and led to the books of Arius and his followers being burned by Roman emperors, and the practice of burning heretical texts continued after Nicaea. This act of destruction was a way to suppress and erase dissenting theological viewpoints.

The council banned Gnostic cults, including Arianism, and led to the books of Arius and his followers being burned by Roman emperors, and the practice of burning heretical texts continued after Nicaea. This act of destruction was a way to suppress and erase dissenting theological viewpoints.

This council also began the arduous task of choosing the gospels that were codified by the Church. In 325 and 333 CE Emperor Constantine ordered any gospels outside the chosen canon of the four to be burned. This suggests that many of the gospels previously banned were still in circulation.

The image depicts the burning of the works of Arius by order of the Emperor Constantine during the First Council of Nicaea. Engraving by Carel Christiaan Antony Last in 1835.

To prove Jesus’ divinity, the Church sought to erase all trace of his humanity. This included awkward details of his natural birth, his siblings, his marriage to Mary Magdalene and their children. Redactions were made where possible to edit scriptures, and the most incriminating scriptures were targeted for destruction.

But I wonder whether this was successful. Considering her legacy was thriving in France and Spain, I don’t believe the council was as thorough as intended. Clearly the Church was not able to erase her, so they pivoted and tried rebranding her instead.

But how?

Ruining Mary Magdalene’s Reputation

The Church used a sure-fire way to ruin a woman’s reputation. They did what is always done: they implied she was a slut.

In 591 CE Pope Gregory the Great (c.540-604 CE) in his ‘Homily 25 On the Gospels’ used the story of the unnamed “sinful woman” who anointed Jesus’ feet to condemn Mary Magdalene as a prostitute and a sinner. This image of the anointing of Jesus is from the Cappella Rinuccini by Giovanni da Milano (c.1370).

We are not told explicitly what she has done to be called a sinner, leaving imaginations to run wild. For celibate and cloistered Pope Gregory this inevitably must involve sex. Pope Gregory called her a peccatrix, sinner. Eventually, she came to be called meretrix, prostitute.

Pope Gregory’s homily, with its heady mix of sexual innuendo and mystery, was a winner. It was used for centuries to frame the identity of Mary Magdalene. Incredibly, the Church managed to totally rewrite history and create a version of Mary Magdalene that suited the purposes of the Church. This is the legacy most people are aware of and believe as historic fact.

Often artists depicted Mary Magdalene having a wardrobe malfunction, with her dress slipping to her elbows tantalisingly exposing her upper body with only her hair and a rather large, strategically placed skull protecting her virtue. (For more on the symbolism of the skull see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, and a Skull’). Beside her is an unassuming little jar, another of Mary Magdalene’s symbols. (For more on the jar read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene, the Anointrix’).

Artists loved the heady mixture of mystery and sexuality that this inspired. And so began a tradition of the Penitent Mary who is both repentant but still clearly sexually attractive. Often portraits portray her as a temptress or femme fatale, semi-clad with enough flesh exposed to make her very enticing.

This painting is by Guido Reni of Saint Mary Magdalene the penitent from about 1633, housed in the Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica. Her hand rests uncomfortably on a skull, so although her eyes draw our attention upwards towards the cherubs flying above her, her arm also also draws us inextricably towards the skull. (For more on the symbolism of the skull see my blog: ‘What’s With the Skull, Mary Magdalene?’).

Mary Magdalene became the face of the penitent sinful woman seeking salvation. She was the quintessential bad woman who needed to repent her sins to be forgiven. Like the first woman, Eve, Mary Magdalene became the poster girl for all things wrong and sinful about women in general.

Mary Magdalene was used to make us feel self-loathing for our own body, our own natural needs, and desires. This is the lesson for all born of sin, especially women.

The Madonna-Whore Complex

This weird new genre in art erupted, where Mary Magdalene could be depicted as both devout and sexually enticing. In this image ‘Repentant Mary Magdalene in the Hermitage’ is an oil on canvas painting by Titian from the 1560s, housed in the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, she has the symbols of her practice – the skull and open book. (For more on the symbolism of the book see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene and the Open Book’). But there is so much more inferred. At first glance she is praying, eyes cast towards the heavens. But her expression and the placement of her hands suggests an orgasmic ecstatic state.

In a fascinating article ‘Real men don’t eat strong women: The virgin-Madonna-whore complex updated’ (in ‘The Journal of Psychohistory’ 12(4), 487–495.) Deborah Tanzer describes the Madonna-whore complex. This continues to taint women’s ability to fully express herself or her desires. This complex is the dominant pattern of thought that divides women’s humanity into two neat and tidy categories that don’t overlap: Madonnas and whores. The pure and the tainted. The nurturing and the depraved. The asexual and the sexual. The loved and respected versus the desired.

Deborah Tanzer stated: “women who exhibit the combined qualities of the openness, vulnerability, and playfulness of the virgin; the niceness, tenderness, and empathy of the Madonna or mother; the sexuality of the whore; and (formerly male types of) intelligence, courage, directness, and honesty are often rejected, sought ambivalently, or sought only for some facets by men.” In other words, we are damned if we do, damned if we don’t.

Deborah Tanzer continues “It is argued that fears, wishes, and assumptions about our own and others’ fullness, completeness, and personal entitlement are at the core of this paradox and that limitation and control are the central defences created in attempts to deal with these fears, wishes, and assumptions. Both women’s and men’s defensive flights from wholeness, integration, maturity, and finite mortality are described, including varied childlike behaviours or counter-phobic exaggeration of single parts of functions into culturally idealised images (e.g., virgin, madonna, whore and smart man, omnipotent father, tutor of virgin).”

The Madonna archetype imprisoned women into impossible assumptions that made women’s intelligence an obscenity. Instead of being encouraged, women were held captive inside their gilded cages, movement and entertainment restricted to what was sanctioned by the men around her.

The Madonna archetype imprisoned women into impossible assumptions that made women’s intelligence an obscenity. Instead of being encouraged, women were held captive inside their gilded cages, movement and entertainment restricted to what was sanctioned by the men around her.

Holding a view of women as either virgins or whores not only limits women’s sexual expression, but it creates a false dichotomy and impossible standards. It also strips women of their right to pleasure in the same way that men simply expect it, without question. Living within the Madonna-whore complex was yet another way the patriarchy worked to hold women in impossible standards.

Clutching her breast, trying to hold up her dress in an unsuccessful attempt at modesty, here the ‘Penitent Magdalene’ is depicted by an unknown artist after Cerezo, Mateo, the younger, a Spanish painter, 1637-1666. Still her gesture is towards this curious open book.

The Myth of Mary Magdalene

Images of Mary Magdalene whisper of secret wisdom, with her skull and her open book. Here ‘La Magdalena Penitente’ is pained by Luca Giordano. Unfortunately, these artists loved the titillation of Mary Magdalene struggling to cover her breasts.

The accusation that Mary Magdalene was a repentant prostitute hangs on the dual use of her legend to discredit sexuality in general and disempower women in particular.

The myth of Mary Magdalene has been used in conflicts that defined the Christian Church over attitudes toward the material world, focused on sexuality. Whether in the time of Constantine, the Counter-Reformation, the Romantic era, or the Industrial Age reinventions of Mary Magdalene has played a role.

The myth of Mary Magdalene has been used to justify the authority of an all-male clergy and champion celibacy. She has been used to brand theological diversity as heresy. She has been used to sublimate courtly love and unleash chivalrous violence. She has been used to market sainthood.

For two thousand years the Church projected onto Mary Magdalene that she was a prostitute. Imagine living under that level of projection. Most of us can identify with the feminine pain body, although I don’t think it’s as severe as it was historically. Women could not claim our magic as women or claim ourselves as medicine women for fear of being called out as a witch.

The Magdalene Wound also speaks to the grief of losing her beloved Jesus who were so close and then he was sacrificed on behalf of the mission they came in to do. There’s abandonment inside the feminine pain body. Whether it’s through a tragic leaving or a good leaving people we know leave.

The Magdalene Wound also speaks to the grief of losing her beloved Jesus who were so close and then he was sacrificed on behalf of the mission they came in to do. There’s abandonment inside the feminine pain body. Whether it’s through a tragic leaving or a good leaving people we know leave.

We carry the wounds of being abandoned and so Mary Magdalene has the capacity to show us where in our feminine pain body or to show us or mirror back to us our own feminine pain body.

Mary Magdalene was forever cast as a marginal character in the famous tale – a fallen, shameful and sinful woman. In the Middle Ages Mary Magdalene became the patron saint of repentant prostitutes. By the eighteenth century, reformation houses for women prostitutes and women considered fallen were called Magdalen Houses.

This depiction of the ‘Penitent Magdalene’ is a 1576–1578 painting by El Greco housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest.

The idea of a fallen woman was coined in the nineteenth century in Britain. The idiom was probably inspired by women who, with the reputation ruined, saw no option but to throw themselves off bridges to drown, literally falling to their death.

Falling from grace traditionally refers to a loss of status, respect, prestige, or support, but became associated with a woman’s loss of chastity and promiscuity.

In blatant hypocrisy, the gentlemen who kept their female relatives, daughters, and wives far from prying eyes and far from the clutches of lecherous men, were the same gentlemen who frequented the houses of ill repute. These gentlemen preached purity and chastity to their daughters while deflowering the most vulnerable in society.

In blatant hypocrisy, the gentlemen who kept their female relatives, daughters, and wives far from prying eyes and far from the clutches of lecherous men, were the same gentlemen who frequented the houses of ill repute. These gentlemen preached purity and chastity to their daughters while deflowering the most vulnerable in society.

In ‘When God Had a Wife: the rise and fall of the Sacred Feminine in the Judeo-Christian Tradition’ Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince conclude the misrepresentation of Mary Magdalene as a fallen woman continued so long because “her myth was still useful in keeping uppity women down. It was very convenient to have a penitent, usually presented as so hysterical with grief that she never had a moment’s peace for the rest of her life.”

This ‘Penitent Magdalene’ is by by Paolo Veronese c.1583.

The Mistranslation

Was Pope Gregory’s homily based on a mistranslation?

Mary Magdalene was most likely the unnamed “woman in the city, who was a sinner” anointed Jesus’ feet with ointment (Luke 7:36-50). The word sinner was translated from the Greek hamartolos. This is the word interpreted to call Mary Magdalene a prostitute. The word for harlot is porin and is used throughout the Gospel of Luke.

Mary Magdalene was most likely the unnamed “woman in the city, who was a sinner” anointed Jesus’ feet with ointment (Luke 7:36-50). The word sinner was translated from the Greek hamartolos. This is the word interpreted to call Mary Magdalene a prostitute. The word for harlot is porin and is used throughout the Gospel of Luke.

Harmartolos referred to someone who had transgressed Civil Jewish Law, rather than a moral sinner. In ‘When God Had a Wife: the rise and fall of the Sacred Feminine in the Judeo-Christian Tradition’ Lynn Picknett and Clive Prince translate hamartolos as an archery term meaning to miss the target that “applied to Jews who failed to keep the Law and also those who needn’t observe it simply because they were not Jewish”.

I went searching for more proof of the inherent sinfulness of these women based on the customs of first century Palestine. In Luke the host of the anointing scene was Simon was a Pharisee. The Pharisees studied the Scripture, were highly self-disciplined, tithed scrupulously and had a reputation for being godly men.

Simon the Pharisee was complaining that this unnamed woman has rejected the strict Jewish religious obligation he upheld. Women were forbidden to speak to strangers. Bursting into rooms uninvited Mary was risking not just criticism but punishment.

According to Jewish civil law, women had to have their hair covered and wear a veil in public. Yet Mary dried Jesus’ feet with her hair so her hair was unbound or at least uncovered. This was enough of a sin for her head to be shaved!

For Mary of Magdala to travel so freely suggests she was not married. In first century, Palestine it would have been unthinkable for an unmarried woman to travel unaccompanied with a religious teacher and his followers. More perplexing still is the closeness she shared with Jesus.

This would have been grounds for adultery for an unmarried woman. Mary Magdalene was the only woman in the Bible not defined by her relationship to any man as his daughter, mother, wife or daughter. If Mary Magdalene had married, obedience to her husband was required from her as part of her religious obligation.

Her testimony was considered legally invalid so she couldn’t receive a divorce. Leaving her husband was considered a sin in Jewish civil law, an offence. It was almost unthinkable. If she had chosen not to marry, she was also still a sinner according to Jewish civil law.

Mary Magdalene was independently wealthy and a financial supporter of Jesus, spending her money where she saw fit. Although it wasn’t unusual for women to travel with a religious teacher, it was scandalous. It is hard to imagine how Mary was able to be amongst Jesus’ followers without being married to one of the disciples.

This image made from tempera and gold leaf on paper is by pseudo Jacopino di Francesco of Mary Magdalene Washing Christ’s Feet from around 1325-1330.

Mary Magdalene was a renegade in her own time – a woman who chose to walk the road less travelled and raised a few eyebrows along the way.

Suddenly I could see how much in common I had with Mary Magdalene. Mary Magdalene was looking for her identity beyond what society forced upon her. She searched for acceptance, for love, for her god.

Mary Magdalene searched for her own personal connection with the God of her ancestors, exploring beyond what others told her. She searched for a new way of being that was more authentically true for her. In the process, Mary disrupted the social narrative of her culture.

Mary Magdalene rebelled against the social cues and rules of her society. Mary Magdalene threw caution to the wind and headed off into unknown territory, learning as she went.

Mary Magdalene became hamartolos, an outcast, an outsider. Mary Magdalene had abandoned Jewish civil law and had become an outcaste of Jewish ways. She was a strange woman, a hamartolos, who did not follow the Jewish customs or the Hebrew religion.

Of course, being hamartolos does not make Mary Magdalene a whore. (For more read my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene the Rebel’).

The Lie Retracted

What is curious is that the background of many of these paintings is of nature, and often look similar. This ‘Penitent Mary Magdalen in a Landscape’, artist unknown, was painted between 1600-1699, now housed in Kedleston Hall. Are these artists hinting at the connection of Mary Magdalene and nature? Our natural intuition and instinctual nature? Or were they aware of the French legends of Mary Magdalene meditating in a cave in Gaul at La St Baume outside Marseille in southern France? Was these secret knowledge of her ministry that the artists passed down amongst themselves or in secret organisations? (For more on the French legends see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

What is curious is that the background of many of these paintings is of nature, and often look similar. This ‘Penitent Mary Magdalen in a Landscape’, artist unknown, was painted between 1600-1699, now housed in Kedleston Hall. Are these artists hinting at the connection of Mary Magdalene and nature? Our natural intuition and instinctual nature? Or were they aware of the French legends of Mary Magdalene meditating in a cave in Gaul at La St Baume outside Marseille in southern France? Was these secret knowledge of her ministry that the artists passed down amongst themselves or in secret organisations? (For more on the French legends see my blog: ‘Mary Magdalene in Gaul’).

In 1969 the Roman Missal (determining Latin Rite liturgy) differentiated the three Mary’s: Mary the sinner, Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene. This meant the Church contradicted themselves by conflating the penitent sinner with Mary Magdalene.

The 1969 canonisation of Mary Magdalene brought the Western Roman Catholic Church in sync with the Eastern Orthodox Church who have believed there were three separate Mary’s. Interestingly, almost all iconography of Mary Magdalene depicts her holding an alabaster jar, despite this being contrary to Eastern doctrine that Mary of Bethany and Mary Magdalene were not the same.

This Roman Missal in 1969 made her canonical status formally recognised although this status still treated her as a penitent sinner, a reformed prostitute, even though nowhere in the gospels was this stated. Mary Magdalene was conflated with the conveniently unnamed woman “taken in adultery” who Jesus refused to punish and was allowed to “go, and sin no more” (John 8:1-11).

This Roman Missal in 1969 made her canonical status formally recognised although this status still treated her as a penitent sinner, a reformed prostitute, even though nowhere in the gospels was this stated. Mary Magdalene was conflated with the conveniently unnamed woman “taken in adultery” who Jesus refused to punish and was allowed to “go, and sin no more” (John 8:1-11).

Mary Magdalene was made a saint on her own feast day on 22 July, 1969. This date was not picked arbitrarily but confirmed to tradition upheld in the West since at least from the eight century.

I love how contemporary this ‘Penitent Magdalene’ oil on canvas painting appears, even though Carlo Dolci actually offered his depiction in around 1670. I can see her pouring her heart out in prayer, accompanied by her icons – the skull and jar of ointment.

In 2016, the Catholic Church finally rescinded its two-thousand-year-old stance on Mary Magdalene, declaring that she was not a prostitute after all, but an Apostle. In fact, the Pope went so far as to name her The First Apostle, since she was the first to encounter the resurrected Christ and broadcast that message.

It took until 2017 for the Catholic Church to finally come clean and admit that Mary Magdalene was not the penitent sinner that the Church had been portraying for a thousand years.

On May 17, 2017, Pope Francis made a revealing proclamation to the General Audience in Vatican City, referring to Mary Magdalene as “an Apostle of the new and greatest hope”.

On May 17, 2017, Pope Francis made a revealing proclamation to the General Audience in Vatican City, referring to Mary Magdalene as “an Apostle of the new and greatest hope”.

Pope Francis said: “By calling Mary Magdalene by name after his resurrection… Mary becomes an apostle of hope for the world, announcing the Lord’s rising. Mary: the revolution of her life, the revolution destined to transform the existence of every man and woman, begins with a name that echoes in the garden of the empty tomb. So that woman, who is the first to encounter Jesus…now has become an apostle of the new and greatest hope.”

The Vatican decided that like oh no never mind she wasn’t actually a prostitute and we’re going to honour her with a feast day, but they didn’t go as far as saying that she was Jesus’ consort and that they taught each other she was she was no doubt a high priestess from the lineage of Isis which is the lineage of the red thread. She spent time learning in in Egypt. Anna, the grandmother of Jesus was part of the Mary lineage.

This more serious portrait by Orazio Gentileschi of ‘Saint Mary Magdalen in Penitence’, depicted inside a cave.

Feature Image: ‘Penitent Magdalene’ by Tintoretto